year

stringdate 1961-01-01 00:00:00

2025-01-01 00:00:00

⌀ | tier

stringclasses 5

values | problem_label

stringclasses 119

values | problem_type

stringclasses 13

values | exam

stringclasses 28

values | problem

stringlengths 87

2.77k

| solution

stringlengths 834

13k

| metadata

dict | problem_tokens

int64 50

903

| solution_tokens

int64 500

3.93k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2020

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Determine all positive integers $k$ for which there exist a positive integer $m$ and a set $S$ of positive integers such that any integer $n>m$ can be written as a sum of distinct elements of $S$ in exactly $k$ ways.

|

. We give an alternative proof of the first half of the lemma in the Solution 1 above.

Let $s_{1}<s_{2}<\cdots$ be the elements of $S$. For any positive integer $r$, define $A_{r}(x)=\prod_{n=1}^{r}\left(1+x^{s_{n}}\right)$. For each $n$ such that $m \leq n<s_{r+1}$, all $k$ ways of writing $n$ as a sum of elements of $S$ must only use $s_{1}, \ldots, s_{r}$, so the coefficient of $x^{n}$ in $A_{r}(x)$ is $k$. Similarly the number of ways of writing $s_{r+1}$ as a sum of elements of $S$ without using $s_{r+1}$ is exactly $k-1$. Hence the coefficient of $x^{s_{r+1}}$ in $A_{r}(x)$ is $k-1$.

Fix a $t$ such that $s_{t}>2(m+1)$. Write

$$

A_{t-1}(x)=u(x)+k\left(x^{m+1}+\cdots+x^{s_{t}-1}\right)+x^{s_{t}} v(x)

$$

for some $u(x), v(x)$ where $u(x)$ is of degree at most $m$.

Note that

$$

A_{t+1}(x)=A_{t-1}(x)+x^{s_{t}} A_{t-1}(x)+x^{s_{t+1}} A_{t-1}(x)+x^{s_{t}+s_{t+1}} A_{t-1}(x)

$$

If $s_{t+1}+m+1<2 s_{t}$, we can find the term $x^{s_{t+1}+m+1}$ in $x^{s_{t}} A_{t-1}(x)$ and in $x^{s_{t+1}} A_{t-1}(x)$. Hence the coefficient of $x^{s_{t+1}+m+1}$ in $A_{t+1}(x)$ is at least $2 k$, which is impossible. So $s_{t+1} \geq 2 s_{t}-(m+1)>$ $s_{t}+m+1$.

Now

$$

A_{t}(x)=A_{t-1}(x)+x^{s_{t}} u(x)+k\left(x^{s_{t}+m+1}+\cdots x^{2 s_{t}-1}\right)+x^{2 s_{t}} v(x)

$$

Recall that the coefficent of $x^{s_{t+1}}$ in $A_{t}(x)$ is $k-1$. But if $s_{t}+m+1<s_{t+1}<s_{2 t}$, then the coefficient of $x^{s_{t+1}}$ in $A_{t}(x)$ is at least $k$, which is a contradiction. Therefore $s_{t+1} \geq 2 s_{t}$.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2020_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2"

}

| 55

| 707

|

2020

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Let $\mathbb{Z}$ denote the set of all integers. Find all polynomials $P(x)$ with integer coefficients that satisfy the following property:

For any infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ of integers in which each integer in $\mathbb{Z}$ appears exactly once, there exist indices $i<j$ and an integer $k$ such that $a_{i}+a_{i+1}+\cdots+a_{j}=P(k)$.

|

Part 1: All polynomials with $\operatorname{deg} P=1$ satisfy the given property.

Suppose $P(x)=c x+d$, and assume without loss of generality that $c>d \geq 0$. Denote $s_{i}=a_{1}+a_{2}+$ $\cdots+a_{i}(\bmod c)$. It suffices to show that there exist indices $i$ and $j$ such that $j-i \geq 2$ and $s_{j}-s_{i} \equiv d$ $(\bmod c)$.

Consider $c+1$ indices $e_{1}, e_{2}, \ldots, e_{c+1}>1$ such that $a_{e_{l}} \equiv d(\bmod c)$. By the pigeonhole principle, among the $n+1$ pairs $\left(s_{e_{1}-1}, s_{e_{1}}\right),\left(s_{e_{2}-1}, s_{e_{2}}\right), \ldots,\left(s_{e_{n+1}-1}, s_{e_{n+1}}\right)$, some two are equal, say $\left(s_{m-1}, s_{m}\right)$ and $\left(s_{n-1}, s_{n}\right)$. We can then take $i=m-1$ and $j=n$.

Part 2: All polynomials with $\operatorname{deg} P \neq 1$ do not satisfy the given property.

Lemma: If $\operatorname{deg} P \neq 1$, then for any positive integers $A, B$, and $C$, there exists an integer $y$ with $|y|>C$ such that no value in the range of $P$ falls within the interval $[y-A, y+B]$.

Proof of Lemma: The claim is immediate when $P$ is constant or when $\operatorname{deg} P$ is even since $P$ is bounded from below. Let $P(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+a_{1} x+a_{0}$ be of odd degree greater than 1 , and assume without

loss of generality that $a_{n}>0$. Since $P(x+1)-P(x)=a_{n} n x^{n-1}+\ldots$, and $n-1>0$, the gap between $P(x)$ and $P(x+1)$ grows arbitrarily for large $x$. The claim follows.

Suppose $\operatorname{deg} P \neq 1$. We will inductively construct a sequence $\left\{a_{i}\right\}$ such that for any indices $i<j$ and any integer $k$ it holds that $a_{i}+a_{i+1}+\cdots+a_{j} \neq P(k)$. Suppose that we have constructed the sequence up to $a_{i}$, and $m$ is an integer with smallest magnitude yet to appear in the sequence. We will add two more terms to the sequence. Take $a_{i+2}=m$. Consider all the new sums of at least two consecutive terms; each of them contains $a_{i+1}$. Hence all such sums are in the interval $\left[a_{i+1}-A, a_{i+1}+B\right]$ for fixed constants $A, B$. The lemma allows us to choose $a_{i+1}$ so that all such sums avoid the range of $P$.

Alternate Solution for Part 1: Again, suppose $P(x)=c x+d$, and assume without loss of generality that $c>d \geq 0$. Let $S_{i}=\left\{a_{j}+a_{j+1}+\cdots+a_{i}(\bmod c) \mid j=1,2, \ldots, i\right\}$. Then $S_{i+1}=\left\{s_{i}+a_{i+1}\right.$ $\left.(\bmod c) \mid s_{i} \in S_{i}\right\} \cup\left\{a_{i+1}(\bmod c)\right\}$. Hence $\left|S_{i+1}\right|=\left|S_{i}\right|$ or $S_{i+1}=\left|S_{i}\right|+1$, with the former occuring exactly when $0 \in S_{i}$. Since $\left|S_{i}\right| \leq c$, the latter can only occur finitely many times, so there exists $I$ such that $0 \in S_{i}$ for all $i \geq I$. Let $t>I$ be an index with $a_{t} \equiv d(\bmod c)$. Then we can find a sum of at least two consecutive terms ending at $a_{t}$ and congruent to $d(\bmod c)$.

Alternate Construction when $P(x)$ is constant or of even degree

If $P(x)$ is of even degree, then $P$ is bounded from below or from above. In case of $P$ is constant or bounded from above, then there exists a positive integer $c$ such that $P(x)<c$. Let $\left\{a_{i}\right\}$ be the sequence

$$

0,1,-1,2,3,-2,4,5,-3, \cdots

$$

which is given by $a_{3 n+1}=2 n, a_{3 n+2}=2 n+1, a_{3 n+3}=-(n+1)$ for all $n \geq 0$. Notice that for any $i<j$ we have $a_{i}+\cdots+a_{j} \geq 0$. Then for the sequence $\left\{b_{n}\right\}$ defined by $b_{n}=a_{n}+c$, clearly $b_{i}+\cdots+b_{j} \geq\left(a_{i}+\cdots+a_{j}\right)+2 c>c$ which is out side the range of $P(x)$.

Now if $P$ is bounded from below, there exist a positive integer $c$ such that $P(x)>-c$. In this case, take $b_{n}$ to be $b_{n}=-a_{n}-c$. Then for all $i<j$ we have $b_{i}+\cdots+b_{j} \leq-\left(a_{1}+\cdots a_{n}\right)-2 c<-c$ which is again out side the range of $P(x)$.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2020_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution:"

}

| 103

| 1,448

|

2020

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n \geq 3$ be a fixed integer. The number 1 is written $n$ times on a blackboard. Below the blackboard, there are two buckets that are initially empty. A move consists of erasing two of the numbers $a$ and $b$, replacing them with the numbers 1 and $a+b$, then adding one stone to the first bucket and $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$ stones to the second bucket. After some finite number of moves, there are $s$ stones in the first bucket and $t$ stones in the second bucket, where $s$ and $t$ are positive integers. Find all possible values of the ratio $\frac{t}{s}$.

|

The answer is the set of all rational numbers in the interval $[1, n-1)$. First, we show that no other numbers are possible. Clearly the ratio is at least 1, since for every move, at least one stone is added to the second bucket. Note that the number $s$ of stones in the first bucket is always equal to $p-n$, where $p$ is the sum of the numbers on the blackboard. We will assume that the numbers are written in a row, and whenever two numbers $a$ and $b$ are erased, $a+b$ is written in the place of the number on the right. Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be the numbers on the blackboard from left to right, and let

$$

q=0 \cdot a_{1}+1 \cdot a_{2}+\cdots+(n-1) a_{n}

$$

Since each number $a_{i}$ is at least 1 , we always have

$$

q \leq(n-1) p-(1+\cdots+(n-1))=(n-1) p-\frac{n(n-1)}{2}=(n-1) s+\frac{n(n-1)}{2}

$$

Also, if a move changes $a_{i}$ and $a_{j}$ with $i<j$, then $t$ changes by $\operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right) \leq a_{i}$ and $q$ increases by

$$

(j-1) a_{i}-(i-1)\left(a_{i}-1\right) \geq i a_{i}-(i-1)\left(a_{i}-1\right) \geq a_{i}

$$

Hence $q-t$ never decreases. We may assume without loss of generality that the first move involves the rightmost 1. Then immediately after this move, $q=0+1+\cdots+(n-2)+(n-1) \cdot 2=\frac{(n+2)(n-1)}{2}$ and

$t=1$. So after that move, we always have

$$

\begin{aligned}

t & \leq q+1-\frac{(n+2)(n-1)}{2} \\

& \leq(n-1) s+\frac{n(n-1)}{2}-\frac{(n+2)(n-1)}{2}+1 \\

& =(n-1) s-(n-2)<(n-1) s

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence, $\frac{t}{s}<n-1$. So $\frac{t}{s}$ must be a rational number in $[1, n-1)$.

After a single move, we have $\frac{t}{s}=1$, so it remains to prove that $\frac{t}{s}$ can be any rational number in $(1, n-1)$. We will now show by induction on $n$ that for any positive integer $a$, it is possible to reach a situation where there are $n-1$ occurrences of 1 on the board and the number $a^{n-1}$, with $t$ and $s$ equal to $a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)$ and $a^{n-1}-1$, respectively. For $n=2$, this is clear as there is only one possible move at each step, so after $a-1$ moves $s$ and $t$ will both be equal to $a-1$. Now assume that the claim is true for $n-1$, where $n>2$. Call the algorithm which creates this situation using $n-1$ numbers algorithm $A$. Then to reach the situation for size $n$, we apply algorithm $A$, to create the number $a^{n-2}$. Next, apply algorithm $A$ again and then add the two large numbers, repeat until we get the number $a^{n-1}$. Then algorithm $A$ was applied $a$ times and the two larger numbers were added $a-1$ times. Each time the two larger numbers are added, $t$ increases by $a^{n-2}$ and each time algorithm $A$ is applied, $t$ increases by $a^{n-3}(a-1)(n-2)$. Hence, the final value of $t$ is

$$

t=(a-1) a^{n-2}+a \cdot a^{n-3}(a-1)(n-2)=a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)

$$

This completes the induction.

Now we can choose 1 and the large number $b$ times for any positive integer $b$, and this will add $b$ stones to each bucket. At this point we have

$$

\frac{t}{s}=\frac{a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)+b}{a^{n-1}-1+b}

$$

So we just need to show that for any rational number $\frac{p}{q} \in(1, n-1)$, there exist positive integers $a$ and $b$ such that

$$

\frac{p}{q}=\frac{a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)+b}{a^{n-1}-1+b}

$$

Rearranging, we see that this happens if and only if

$$

b=\frac{q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p\left(a^{n-1}-1\right)}{p-q} .

$$

If we choose $a \equiv 1(\bmod p-q)$, then this will be an integer, so we just need to check that the numerator is positive for sufficiently large $a$.

$$

\begin{aligned}

q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p\left(a^{n-1}-1\right) & >q a^{n-2}(a-1)(n-1)-p a^{n-1} \\

& =a^{n-2}(a(q(n-1)-p)-(n-1))

\end{aligned}

$$

which is positive for sufficiently large $a$ since $q(n-1)-p>0$.

Alternative solution for the upper bound. Rather than starting with $n$ occurrences of 1 , we may start with infinitely many 1 s , but we are restricted to having at most $n-1$ numbers which are not equal to 1 on the board at any time. It is easy to see that this does not change the problem. Note also that we can ignore the 1 we write on the board each move, so the allowed move is to rub off two numbers and write their sum. We define the width and score of a number on the board as follows. Colour that number red, then reverse every move up to that point all the way back to the situation when the numbers are all 1 s . Whenever a red number is split, colour the two replacement numbers

red. The width of the original number is equal to the maximum number of red integers greater than 1 which appear on the board at the same time. The score of the number is the number of stones which were removed from the second bucket during these splits. Then clearly the width of any number is at most $n-1$. Also, $t$ is equal to the sum of the scores of the final numbers. We claim that if a number $p>1$ has a width of at most $w$, then its score is at most $(p-1) w$. We will prove this by strong induction on $p$. If $p=1$, then clearly $p$ has a score of 0 , so the claim is true. If $p>1$, then $p$ was formed by adding two smaller numbers $a$ and $b$. Clearly $a$ and $b$ both have widths of at most $w$. Moreover, if $a$ has a width of $w$, then at some point in the reversed process there will be $w$ numbers in the set $\{2,3,4, \ldots\}$ that have split from $a$, and hence there can be no such numbers at this point which have split from $b$. Between this point and the final situation, there must always be at least one number in the set $\{2,3,4, \ldots\}$ that split from $a$, so the width of $b$ is at most $w-1$. Therefore, $a$ and $b$ cannot both have widths of $w$, so without loss of generality, $a$ has width at most $w$ and $b$ has width at most $w-1$. Then by the inductive hypothesis, $a$ has score at most $(a-1) w$ and $b$ has score at most $(b-1)(w-1)$. Hence, the score of $p$ is at most

$$

\begin{aligned}

(a-1) w+(b-1)(w-1)+\operatorname{gcd}(a, b) & \leq(a-1) w+(b-1)(w-1)+b \\

& =(p-1) w+1-w \\

& \leq(p-1) w .

\end{aligned}

$$

This completes the induction.

Now, since each number $p$ in the final configuration has width at most $(n-1)$, it has score less than $(n-1)(p-1)$. Hence the number $t$ of stones in the second bucket is less than the sum over the values of $(n-1)(p-1)$, and $s$ is equal to the sum of the the values of $(p-1)$. Therefore, $\frac{t}{s}<n-1$.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 5.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2020_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution:"

}

| 151

| 2,136

|

2021

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

For a polynomial $P$ and a positive integer $n$, define $P_{n}$ as the number of positive integer pairs $(a, b)$ such that $a<b \leq n$ and $|P(a)|-|P(b)|$ is divisible by $n$.

Determine all polynomial $P$ with integer coefficients such that for all positive integers $n, P_{n} \leq 2021$.

|

There are two possible families of solutions:

- $P(x)=x+d$, for some integer $d \geq-2022$.

- $P(x)=-x+d$, for some integer $d \leq 2022$.

Suppose $P$ satisfies the problem conditions. Clearly $P$ cannot be a constant polynomial. Notice that a polynomial $P$ satifies the conditions if and only if $-P$ also satisfies them. Hence, we may assume the leading coefficient of $P$ is positive. Then, there exists positive integer $M$ such that $P(x)>0$ for $x \geq M$.

Lemma 1. For any positive integer $n$, the integers $P(1), P(2), \ldots, P(n)$ leave pairwise distinct remainders upon division by $n$.

Proof. Assume for contradiction that this is not the case. Then, for some $1 \leq y<z \leq n$, there exists $0 \leq r \leq n-1$ such that $P(y) \equiv P(z) \equiv r(\bmod n)$. Since $P(a n+b) \equiv P(b)(\bmod n)$ for all $a, b$ integers, we have $P(a n+y) \equiv P(a n+z) \equiv r(\bmod n)$ for any integer $a$. Let $A$ be a positive integer such that $A n \geq M$, and let $k$ be a positive integer such that $k>2 A+2021$. Each of the $2(k-A)$ integers $P(A n+y), P(A n+z), P((A+1) n+y), P((A+1) n+z), \ldots, P((k-1) n+y), P((k-1) n+z)$ leaves one of the $k$ remainders

$$

r, n+r, 2 n+r, \ldots,(k-1) n+r

$$

upon division by $k n$. This implies that at least $2(k-A)-k=k-2 A$ (possibly overlapping) pairs leave the same remainder upon division by $k n$. Since $k-2 A>2021$ and all of the $2(k-A)$ integers are positive, we find more than 2021 pairs $a, b$ with $a<b \leq k n$ for which $|P(b)|-|P(a)|$ is divisible by $k n$-hence, $P_{k n}>2021$, a contradiction.

Next, we show that $P$ is linear. Assume that this is not the case, i.e., $\operatorname{deg} P \geq 2$. Then we can find a positive integer $k$ such that $P(k)-P(1) \geq k$. This means that among the integers $P(1), P(2), \ldots, P(P(k)-P(1))$, two of them, namely $P(k)$ and $P(1)$, leave the same remainder upon division by $P(k)-P(1)$ - contradicting the lemma (by taking $n=P(k)-P(1)$ ). Hence, $P$ must be linear.

We can now write $P(x)=c x+d$ with $c>0$. We prove that $c=1$ by two ways.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2021_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution "

}

| 92

| 737

|

2021

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

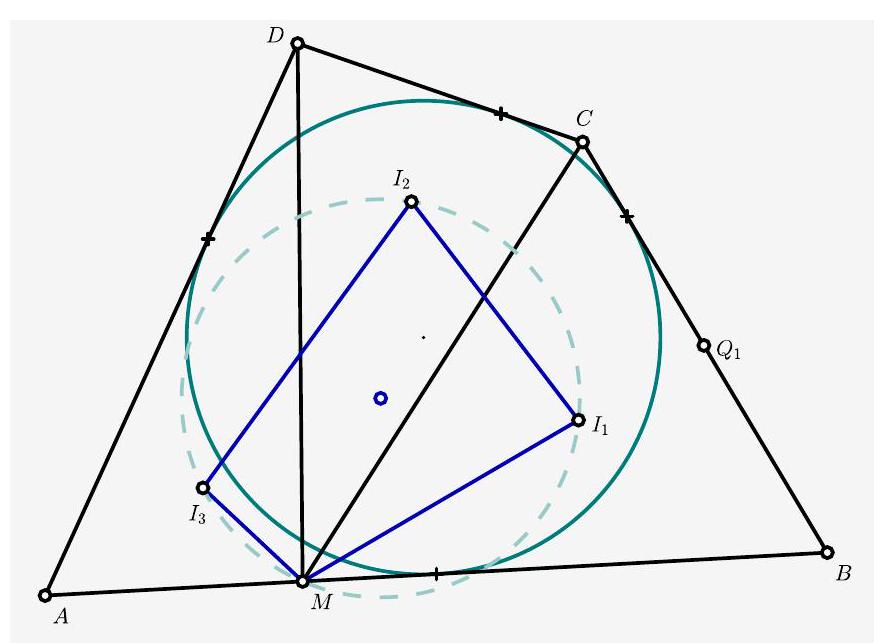

Let $A B C D$ be a cyclic convex quadrilateral and $\Gamma$ be its circumcircle. Let $E$ be the intersection of the diagonals $A C$ and $B D$, let $L$ be the center of the circle tangent to sides $A B, B C$, and $C D$, and let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ of $\Gamma$ not containing $A$ and $D$. Prove that the excenter of triangle $B C E$ opposite $E$ lies on the line $L M$.

|

Let $L$ be the intersection of the bisectors of $\angle A B C$ and $\angle B C D$. Let $N$ be the $E$-excenter of $\triangle B C E$. Let $\angle B A C=\angle B D C=\alpha, \angle D B C=\beta$ and $\angle A C B=\gamma$.

We have the following:

$$

\begin{array}{r}

\angle C B L=\frac{1}{2} \angle A B C=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \alpha-\frac{1}{2} \gamma \text { and } \angle B C L=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \alpha-\frac{1}{2} \beta, \\

\angle C B N=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \beta \text { and } \angle B C N=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \gamma, \\

\angle M B L=\angle M B C+\angle C B L=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \gamma \text { and } \angle M C L=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \beta, \\

\angle L C N=\angle L B N=180^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2}(\alpha+\beta+\gamma) .

\end{array}

$$

Applying the sine rule to $\triangle M B L$ and $\triangle M C L$ we obtain

$$

\frac{M B}{M L}=\frac{M C}{M L}=\frac{\sin \angle B L M}{\sin \angle M B L}=\frac{\sin \angle C L M}{\sin \angle M C L}

$$

It follows that

$$

\frac{\sin \angle B L M}{\sin \angle C L M}=\frac{\sin \angle M B L}{\sin \angle M C L}=\frac{\cos (\gamma / 2)}{\cos (\beta / 2)}

$$

Now

$$

\frac{\sin \angle B L M}{\sin \angle M L C} \cdot \frac{\sin \angle L C N}{\sin \angle N C B} \cdot \frac{\sin \angle N B C}{\sin \angle N B L}=\frac{\cos (\gamma / 2)}{\cos (\beta / 2)} \cdot \frac{\sin \left(90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \beta\right)}{\sin \left(90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \gamma\right)}=1

$$

Hence $L M, B N, C N$ are concurrent and therefore $L, M, N$ are collinear.

## Alternative proof

We proceed similarly as above until the equation (1).

We use the following lemma.

Lemma: If $\pi>\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta>0, \alpha+\beta=\gamma+\delta<\pi$, and $\frac{\sin \alpha}{\sin \beta}=\frac{\sin \gamma}{\sin \delta}$, then $\alpha=\gamma$ and $\beta=\delta$.

Proof of Lemma: Let $\theta=\alpha+\beta=\gamma+\delta$. Then $\frac{\sin (\theta-\beta)}{\sin \beta}=\frac{\sin (\theta-\delta)}{\sin \delta}$.

$$

\begin{gathered}

\Longleftrightarrow \sin (\theta-\beta) \sin \delta=\sin (\theta-\delta) \sin \beta \\

\Longleftrightarrow(\sin \theta \cos \beta-\sin \beta \cos \theta) \sin \delta=(\sin \theta \cos \delta-\sin \delta \cos \theta) \sin \beta \\

\Longleftrightarrow \sin \theta \cos \beta \sin \delta=\sin \theta \cos \delta \sin \beta \\

\Longleftrightarrow \sin \theta \sin (\beta-\delta)=0

\end{gathered}

$$

Since $0<\theta<\pi$, then $\sin \theta \neq 0$. Therefore, $\sin (\beta-\delta)=0$, and we must have $\beta=\delta$.

Applying the sine rule to $\triangle N B L$ and $\triangle N C L$ we obtain

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{N B}{N L}=\frac{\sin \angle B L N}{\sin \angle L B N} \\

& \frac{N C}{N L}=\frac{\sin \angle C L N}{\sin \angle L C N}

\end{aligned}

$$

Since $\angle L B N=\angle L C N$, it follows that

$$

\frac{\sin \angle B L N}{\sin \angle C L N}=\frac{N B}{N C}=\frac{\sin \angle B C N}{\sin \angle C B N}=\frac{\cos (\gamma / 2)}{\cos (\beta / 2)}=\frac{\sin \angle B L M}{\sin \angle C L M}

$$

By the lemma, it is concluded that $\angle B L M=\angle B L N$ and $\angle C L M=\angle C L N$. Therefore, $L, M, N$ are collinear.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2021_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 120

| 1,171

|

2021

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Given a $32 \times 32$ table, we put a mouse (facing up) at the bottom left cell and a piece of cheese at several other cells. The mouse then starts moving. It moves forward except that when it reaches a piece of cheese, it eats a part of it, turns right, and continues moving forward. We say that a subset of cells containing cheese is good if, during this process, the mouse tastes each piece of cheese exactly once and then falls off the table. Show that:

(a) No good subset consists of 888 cells.

(b) There exists a good subset consisting of at least 666 cells.

|

(a) For the sake of contradiction, assume a good subset consisting of 888 cells exists. We call those cheese-cells and the other ones gap-cells. Observe that since each cheese-cell is visited once, each gap-cell is visited at most twice (once vertically and once horizontally). Define a finite sequence $s$ whose $i$-th element is $C$ if the $i$-th step of the mouse was onto a cheese-cell, and $G$ if it was onto a gap-cell. By assumption, $s$ contains $888 C$ 's. Note that $s$ does not contain a contiguous block of 4 (or more) $C$ 's. Hence $s$ contains at least $888 / 3=296$ such $C$-blocks and thus at least $295 G^{\prime}$ 's. But since each gap-cell is traversed at most twice, this implies there are at least $\lceil 295 / 2\rceil=148$ gap-cells, for a total of $888+148=1036>32^{2}$ cells, a contradiction.

(b) Let $L_{i}, X_{i}$ be two $2^{i} \times 2^{i}$ tiles that allow the mouse to "turn left" and "cross", respectively. In detail, the "turn left" tiles allow the mouse to enter at its bottom left cell facing up and to leave at its bottom left cell facing left. The "cross" tiles allow the mouse to enter at its top right facing down and leave at its bottom left facing left, while also to enter at its bottom left facing up and leave at its top right facing right.

(a) Basic tiles

(b) Inductive construction

(c) $16 \times 16$

Note that given two $2^{i} \times 2^{i}$ tiles $L_{i}, X_{i}$ we can construct larger $2^{i+1} \times 2^{i+1}$ tiles $L_{i+1}, X_{i+1}$ inductively as shown on in (b). The construction works because the path intersects itself (or the other path) only inside the smaller $X$-tiles where it works by induction.

For a tile $T$, let $|T|$ be the number of pieces of cheese in it. By straightforward induction, $\left|L_{i}\right|=\left|X_{i}\right|+1$ and $\left|L_{i+1}\right|=4 \cdot\left|L_{i}\right|-1$. From the initial condition $\left|L_{1}\right|=3$. We now easily compute $\left|L_{2}\right|=11,\left|L_{3}\right|=43,\left|L_{4}\right|=171$, and $\left|L_{5}\right|=683$. Hence we get the desired subset.

## Another proof of (a).

Let $X_{N}$ be the largest possible density of cheese-cells in a good subset on an $N \times N$ table. We will show that $X_{N} \leq 4 / 5+o(1)$. Specifically, this gives $X_{32} \leq 817 / 1024$. We look at the (discrete analogue) of the winding number of the trajectory of the mouse. Since the mouse enters and leaves the table, for every 4 right turns in its trajectory there has to be a self-crossing. But each self-crossing requires a different empty square, hence $X_{N} \leq 4 / 5$.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2021_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution."

}

| 137

| 798

|

2021

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Determine all functions $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ such that $f(f(a)-b)+b f(2 a)$ is a perfect square for all integers $a$ and $b$.

|

.

There are two families of functions which satisfy the condition:

(1) $f(n)= \begin{cases}0 & \text { if } n \text { is even, and } \\ \text { any perfect square } & \text { if } n \text { is odd }\end{cases}$

(2) $f(n)=n^{2}$, for every integer $n$.

It is straightforward to verify that the two families of functions are indeed solutions. Now, suppose that f is any function which satisfies the condition that $f(f(a)-b)+b f(2 a)$ is a perfect square for every pair $(a, b)$ of integers. We denote this condition by $\left(^{*}\right)$. We will show that $f$ must belong to either Family (1) or Family (2).

Claim 1. $f(0)=0$ and $f(n)$ is a perfect square for every integer $n$.

Proof. Plugging $(a, b) \rightarrow(0, f(0))$ in $\left(^{*}\right)$ shows that $f(0)(f(0)+1)=z^{2}$ for some integer $z$. Thus, $(2 f(0)+1-2 z)(2 f(0)+1+2 z)=1$. Therefore, $f(0)$ is either -1 or 0.

Suppose, for sake of contradiction, that $f(0)=-1$. For any integer $a$, plugging $(a, b) \rightarrow(a, f(a))$ implies that $f(a) f(2 a)-1$ is a square. Thus, for each $a \in \mathbb{Z}$, there exists $x \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $f(a) f(2 a)=x^{2}+1$ This implies that any prime divisor of $f(a)$ is either 2 or is congruent to $1(\bmod 4)$, and that $4 \nmid f(a)$, for every $a \in \mathbb{Z}$.

Plugging $(a, b) \rightarrow(0,3)$ in $\left(^{*}\right)$ shows that $f(-4)-3$ is a square. Thus, there is $y \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $f(-4)=y^{2}+3$. Since $4 \nmid f(-4)$, we note that $f(-4)$ is a positive integer congruent to $3(\bmod 4)$, but any prime dividing $f(-4)$ is either 2 or is congruent to $1(\bmod 4)$. This gives a contradiction. Therefore, $f(0)$ must be 0 .

For every integer $n$, plugging $(a, b) \rightarrow(0,-n)$ in $\left(^{*}\right)$ shows that $f(n)$ is a square.

Replacing $b$ with $f(a)-b$, we find that for all integers $a$ and $b$,

$$

f(b)+(f(a)-b) f(2 a) \text { is a square. }

$$

Now, let $S$ be the set of all integers $n$ such that $f(n)=0$. We have two cases:

- Case 1: $S$ is unbounded from above.

We claim that $f(2 n)=0$ for any integer $n$. Fix some integer $n$, and let $k \in S$ with $k>f(n)$. Then, plugging $(a, b) \mapsto(n, k)$ in $\left({ }^{* *}\right)$ gives us that $f(k)+(f(n)-k) f(2 n)=(f(n)-k) f(2 n)$ is a square. But $f(n)-k<0$ and $f(2 n)$ is a square by Claim 1. This is possible only if $f(2 n)=0$. In summary, $f(n)=0$ whenever $n$ is even and Claim 1 shows that $f(n)$ is a square whenever $n$ is odd.

- Case 2: $S$ is bounded from above.

Let $T$ be the set of all integers $n$ such that $f(n)=n^{2}$. We show that $T$ is unbounded from above. In fact, we show that $\frac{p+1}{2} \in T$ for all primes $p$ big enough.

Fix a prime number $p$ big enough, and let $n=\frac{p+1}{2}$. Plugging $(a, b) \mapsto(n, 2 n)$ in ( $\left.{ }^{* *}\right)$ shows us that $f(2 n)(f(n)-2 n+1)$ is a square for any integer $n$. For $p$ big enough, we have $2 n \notin S$, so $f(2 n)$ is a non-zero square. As a result, when $p$ is big enough, $f(n)$ and $f(n)-2 n+1=f(n)-p$ are both squares. Writing $f(n)=k^{2}$ and $f(n)-p=m^{2}$ for some $k, m \geq 0$, we have

$$

(k+m)(k-m)=k^{2}-m^{2}=p \Longrightarrow k+m=p, k-m=1 \Longrightarrow k=n, m=n-1

$$

Thus, $f(n)=k^{2}=n^{2}$, giving us $n=\frac{p+1}{2} \in T$.

Next, for all $k \in T$ and $n \in \mathbb{Z}$, plugging $(a, b) \mapsto(n, k)$ in $(* *)$ shows us that $k^{2}+(f(n)-k) f(2 n)$ is a square. But that means $(2 k-f(2 n))^{2}-\left(f(2 n)^{2}-4 f(n) f(2 n)\right)=4\left(k^{2}+(f(n)-k) f(2 n)\right)$ is also a square. When $k$ is large enough, we have $\left|f(2 n)^{2}-4 f(n) f(2 n)\right|+1<|2 k-f(2 n)|$. As a result, we must have $f(2 n)^{2}=4 f(n) f(2 n)$ and thus $f(2 n) \in\{0,4 f(n)\}$ for all integers $n$.

Finally, we prove that $f(n)=n^{2}$ for all integers $n$. Fix $n$, and take $k \in T$ big enough such that $2 k \notin S$. Then, we have $f(k)=k^{2}$ and $f(2 k)=4 f(k)=4 k^{2}$. Plugging $(a, b) \mapsto(k, n)$ to $(* *)$ shows us that $f(n)+\left(k^{2}-n\right) 4 k^{2}=\left(2 k^{2}-n\right)^{2}+\left(f(n)-n^{2}\right)$ is a square. Since $T$ is unbounded from above, we can take $k \in T$ such that $2 k \notin S$ and also $\left|2 k^{2}-n\right|>\left|f(n)-n^{2}\right|$. This forces $f(n)=n^{2}$, giving us the second family of solution.

## Another approach of Case 1.

Claim 2. One of the following is true.

(i) For every integer $n, f(2 n)=0$.

(ii) There exists an integer $K>0$ such that for every integer $n \geq K, f(n)>0$.

Proof. Suppose that there exists an integer $\alpha \neq 0$ such that $f(2 \alpha)>0$. We claim that for every integer $n \geq f(\alpha)+1$, we have $f(n)>0$.

For every $n \geq f(\alpha)+1$, plugging $(a, b) \rightarrow(\alpha, f(\alpha)-n)$ in $\left(^{*}\right)$ shows that $f(n)+(f(\alpha)-n) f(2 \alpha)$ is a square, and in particular, is non-negative. Hence, $f(n) \geq(n-f(\alpha)) f(2 \alpha)>0$, as desired.

If $f$ belongs to Case (i), Claim 1 shows that $f$ belongs to Family (1).

If $f$ belongs to Case (ii), then $S$ is bounded from above. From Case 2 we get $f(n)=n^{2}$.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 5.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2021_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 50

| 1,913

|

2022

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

Find all pairs $(a, b)$ of positive integers such that $a^{3}$ is a multiple of $b^{2}$ and $b-1$ is a multiple of $a-1$. Note: An integer $n$ is said to be a multiple of an integer $m$ if there is an integer $k$ such that $n=k m$.

|

.2

We will start by showing that there are positive integers $x, c, d$ such that $a=x^{2} c d$ and $b=x^{3} c$. Let $g=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$ so that $a=g d$ and $b=g x$ for some coprime $d$ and $x$. Then, $b^{2} \mid a^{3}$ is equivalent to $g^{2} x^{2} \mid g^{3} d^{3}$, which is equivalent to $x^{2} \mid g d^{3}$. Since $x$ and $d$ are coprime, this implies $x^{2} \mid g$. Hence, $g=x^{2} c$ for some $c$, giving $a=x^{2} c d$ and $b=x^{3} c$ as required.

Now, it remains to find all positive integers $x, c, d$ satisfying

$$

x^{2} c d-1 \mid x^{3} c-1

$$

That is, $x^{3} c \equiv 1\left(\bmod x^{2} c d-1\right)$. Assuming that this congruence holds, it follows that $d \equiv x^{3} c d \equiv x$ $\left(\bmod x^{2} c d-1\right)$. Then, either $x=d$ or $x-d \geq x^{2} c d-1$ or $d-x \geq x^{2} c d-1$.

- If $x=d$ then $b=a$.

- If $x-d \geq x^{2} c d-1$, then $x-d \geq x^{2} c d-1 \geq x-1 \geq x-d$. Hence, each of these inequalities must in fact be an equality. This implies that $x=c=d=1$, which implies that $a=b=1$.

- If $d-x \geq x^{2} c d-1$, then $d-x \geq x^{2} c d-1 \geq d-1 \geq d-x$. Hence, each of these inequalities must in fact be an equality. This implies that $x=c=1$, which implies that $b=1$.

Hence the only solutions are the pairs $(a, b)$ such that $a=b$ or $b=1$. These pairs can be checked to satisfy the given conditions.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 1.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2022_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 76

| 544

|

2022

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Find all positive integers $k<202$ for which there exists a positive integer $n$ such that

$$

\left\{\frac{n}{202}\right\}+\left\{\frac{2 n}{202}\right\}+\cdots+\left\{\frac{k n}{202}\right\}=\frac{k}{2}

$$

where $\{x\}$ denote the fractional part of $x$.

Note: $\{x\}$ denotes the real number $k$ with $0 \leq k<1$ such that $x-k$ is an integer.

|

Denote the equation in the problem statement as $\left(^{*}\right)$, and note that it is equivalent to the condition that the average of the remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 is 101 . Since $\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$ is invariant in each residue class modulo 202 for each $1 \leq i \leq k$, it suffices to consider $0 \leq n<202$.

If $n=0$, so is $\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$, meaning that $(*)$ does not hold for any $k$. If $n=101$, then it can be checked that $\left(^{*}\right)$ is satisfied if and only if $k=1$. From now on, we will assume that $101 \nmid n$.

For each $1 \leq i \leq k$, let $a_{i}=\left\lfloor\frac{i n}{202}\right\rfloor=\frac{i n}{202}-\left\{\frac{i n}{202}\right\}$. Rewriting $\left(^{*}\right)$ and multiplying the equation by 202, we find that

$$

n(1+2+\ldots+k)-202\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{k}\right)=101 k

$$

Equivalently, letting $z=a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{k}$,

$$

n k(k+1)-404 z=202 k

$$

Since $n$ is not divisible by 101 , which is prime, it follows that $101 \mid k(k+1)$. In particular, $101 \mid k$ or $101 \mid k+1$. This means that $k \in\{100,101,201\}$. We claim that all these values of $k$ work.

- If $k=201$, we may choose $n=1$. The remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 are 1,2 , ..., 201, which have an average of 101 .

- If $k=100$, we may choose $n=2$. The remainders when dividing $n, 2 n, \ldots, k n$ by 202 are 2,4 , ..., 200, which have an average of 101.

- If $k=101$, we may choose $n=51$. To see this, note that the first four remainders are $51,102,153$, 2 , which have an average of 77 . The next four remainders $(53,104,155,4)$ are shifted upwards from the first four remainders by 2 each, and so on, until the 25 th set of the remainders ( 99 , $150,201,50)$ which have an average of 125 . Hence, the first 100 remainders have an average of $\frac{77+125}{2}=101$. The 101th remainder is also 101 , meaning that the average of all 101 remainders is 101 .

In conclusion, all values $k \in\{1,100,101,201\}$ satisfy the initial condition.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2022_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 131

| 812

|

2022

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n$ and $k$ be positive integers. Cathy is playing the following game. There are $n$ marbles and $k$ boxes, with the marbles labelled 1 to $n$. Initially, all marbles are placed inside one box. Each turn, Cathy chooses a box and then moves the marbles with the smallest label, say $i$, to either any empty box or the box containing marble $i+1$. Cathy wins if at any point there is a box containing only marble $n$.

Determine all pairs of integers $(n, k)$ such that Cathy can win this game.

|

We claim Cathy can win if and only if $n \leq 2^{k-1}$.

First, note that each non-empty box always contains a consecutive sequence of labeled marbles. This is true since Cathy is always either removing from or placing in the lowest marble in a box. As a consequence, every move made is reversible.

Next, we prove by induction that Cathy can win if $n=2^{k-1}$. The base case of $n=k=1$ is trivial. Assume a victory can be obtained for $m$ boxes and $2^{m-1}$ marbles. Consider the case of $m+1$ boxes and $2^{m}$ marbles. Cathy can first perform a sequence of moves so that only marbles $2^{m-1}, \ldots, 2^{m}$ are left in the starting box, while keeping one box, say $B$, empty. Now move the marble $2^{m-1}$ to box $B$, then reverse all of the initial moves while treating $B$ as the starting box. At the end of that, we will have marbles $2^{m-1}+1, \ldots, 2^{m}$ in the starting box, marbles $1,2, \ldots, 2^{m-1}$ in box $B$, and $m-1$ empty boxes. By repeating the original sequence of moves on marbles $2^{m-1}+1, \ldots, 2^{m}$, using the $m$ boxes that are not box $B$, we can reach a state where only marble $2^{m}$ remains in the starting box. Therefore

a victory is possible if $n=2^{k-1}$ or smaller.

We now prove by induction that Cathy loses if $n=2^{k-1}+1$. The base case of $n=2$ and $k=1$ is trivial. Assume a victory is impossible for $m$ boxes and $2^{m-1}+1$ marbles. For the sake of contradiction, suppose that victory is possible for $m+1$ boxes and $2^{m}+1$ marbles. In a winning sequence of moves, consider the last time a marble $2^{m-1}+1$ leaves the starting box, call this move $X$. After $X$, there cannot be a time when marbles $1, \ldots, 2^{m-1}+1$ are all in the same box. Otherwise, by reversing these moves after $X$ and deleting marbles greater than $2^{m-1}+1$, it gives us a winning sequence of moves for $2^{m-1}+1$ marbles and $m$ boxes (as the original starting box is not used here), contradicting the inductive hypothesis. Hence starting from $X$, marbles 1 will never be in the same box as any marbles greater than or equal to $2^{m-1}+1$.

Now delete marbles $2, \ldots, 2^{m-1}$ and consider the winning moves starting from $X$. Marble 1 would only move from one empty box to another, while blocking other marbles from entering its box. Thus we effectively have a sequence of moves for $2^{m-1}+1$ marbles, while only able to use $m$ boxes. This again contradicts the inductive hypothesis. Therefore, a victory is not possible if $n=2^{k-1}+1$ or greater.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2022_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 127

| 758

|

2022

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Let $a, b, c, d$ be real numbers such that $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=1$. Determine the minimum value of $(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(d-a)$ and determine all values of $(a, b, c, d)$ such that the minimum value is achieved.

|

.1

Since the expression is cyclic, we could WLOG $a=\max \{a, b, c, d\}$. Let

$$

S(a, b, c, d)=(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(d-a)

$$

Note that we have given $(a, b, c, d)$ such that $S(a, b, c, d)=-\frac{1}{8}$. Therefore, to prove that $S(a, b, c, d) \geq$ $-\frac{1}{8}$, we just need to consider the case where $S(a, b, c, d)<0$.

- Exactly 1 of $a-b, b-c, c-d, d-a$ is negative.

Since $a=\max \{a, b, c, d\}$, then we must have $d-a<0$. This forces $a>b>c>d$. Now, let us write

$$

S(a, b, c, d)=-(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(a-d)

$$

Write $a-b=y, b-c=x, c-d=w$ for some positive reals $w, x, y>0$. Plugging to the original condition, we have

$$

(d+w+x+y)^{2}+(d+w+x)^{2}+(d+w)^{2}+d^{2}-1=0(*)

$$

and we want to prove that $w x y(w+x+y) \leq \frac{1}{8}$. Consider the expression $(*)$ as a quadratic in $d$ :

$$

4 d^{2}+d(6 w+4 x+2 y)+\left((w+x+y)^{2}+(w+x)^{2}+w^{2}-1\right)=0

$$

Since $d$ is a real number, then the discriminant of the given equation has to be non-negative, i.e. we must have

$$

\begin{aligned}

4 & \geq 4\left((w+x+y)^{2}+(w+x)^{2}+w^{2}\right)-(3 w+2 x+y)^{2} \\

& =\left(3 w^{2}+2 w y+3 y^{2}\right)+4 x(w+x+y) \\

& \geq 8 w y+4 x(w+x+y) \\

& =4(x(w+x+y)+2 w y)

\end{aligned}

$$

However, AM-GM gives us

$$

w x y(w+x+y) \leq \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x(w+x+y)+2 w y}{2}\right)^{2} \leq \frac{1}{8}

$$

This proves $S(a, b, c, d) \geq-\frac{1}{8}$ for any $a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{R}$ such that $a>b>c>d$. Equality holds if and only if $w=y, x(w+x+y)=2 w y$ and $w x y(w+x+y)=\frac{1}{8}$. Solving these equations gives us $w^{4}=\frac{1}{16}$ which forces $w=\frac{1}{2}$ since $w>0$. Solving for $x$ gives us $x(x+1)=\frac{1}{2}$, and we will get $x=-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ as $x>0$. Plugging back gives us $d=-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}$, and this gives us

$$

(a, b, c, d)=\left(\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}, \frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\right)

$$

Thus, any cyclic permutation of the above solution will achieve the minimum equality.

- Exactly 3 of $a-b, b-c, c-d, d-a$ are negative Since $a=\max \{a, b, c, d\}$, then $a-b$ has to be positive. So we must have $b<c<d<a$. Now, note that

$$

\begin{aligned}

S(a, b, c, d) & =(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(d-a) \\

& =(a-d)(d-c)(c-b)(b-a) \\

& =S(a, d, c, b)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now, note that $a>d>c>b$. By the previous case, $S(a, d, c, b) \geq-\frac{1}{8}$, which implies that

$$

S(a, b, c, d)=S(a, d, c, b) \geq-\frac{1}{8}

$$

as well. Equality holds if and only if

$$

(a, b, c, d)=\left(\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}, \frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\right)

$$

and its cyclic permutation.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 5.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2022_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 5"

}

| 77

| 1,191

|

2022

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Let $a, b, c, d$ be real numbers such that $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=1$. Determine the minimum value of $(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(d-a)$ and determine all values of $(a, b, c, d)$ such that the minimum value is achieved.

|

.2

The minimum value is $-\frac{1}{8}$. There are eight equality cases in total. The first one is

$$

\left(\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}, \frac{1}{4}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4},-\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\right) .

$$

Cyclic shifting all the entries give three more quadruples. Moreover, flipping the sign $((a, b, c, d) \rightarrow$ $(-a,-b,-c,-d)$ ) all four entries in each of the four quadruples give four more equality cases. We then begin the proof by the following optimization:

Claim 1. In order to get the minimum value, we must have $a+b+c+d=0$.

Proof. Assume not, let $\delta=\frac{a+b+c+d}{4}$ and note that

$$

(a-\delta)^{2}+(b-\delta)^{2}+(c-\delta)^{2}+(d-\delta)^{2}<a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}

$$

so by shifting by $\delta$ and scaling, we get an even smaller value of $(a-b)(b-c)(c-d)(d-a)$.

The key idea is to substitute the variables

$$

\begin{aligned}

& x=a c+b d \\

& y=a b+c d \\

& z=a d+b c

\end{aligned}

$$

so that the original expression is just $(x-y)(x-z)$. We also have the conditions $x, y, z \geq-0.5$ because of:

$$

2 x+\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}\right)=(a+c)^{2}+(b+d)^{2} \geq 0

$$

Moreover, notice that

$$

0=(a+b+c+d)^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}+2(x+y+z) \Longrightarrow x+y+z=\frac{-1}{2}

$$

Now, we reduce to the following optimization problem.

Claim 2. Let $x, y, z \geq-0.5$ such that $x+y+z=-0.5$. Then, the minimum value of

$$

(x-y)(x-z)

$$

is $-1 / 8$. Moreover, the equality case occurs when $x=-1 / 4$ and $\{y, z\}=\{1 / 4,-1 / 2\}$.

Proof. We notice that

$$

\begin{aligned}

(x-y)(x-z)+\frac{1}{8} & =\left(2 y+z+\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(2 z+y+\frac{1}{2}\right)+\frac{1}{8} \\

& =\frac{1}{8}(4 y+4 z+1)^{2}+\left(y+\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(z+\frac{1}{2}\right) \geq 0

\end{aligned}

$$

The last inequality is true since both $y+\frac{1}{2}$ and $z+\frac{1}{2}$ are not less than zero.

The equality in the last inequality is attained when either $y+\frac{1}{2}=0$ or $z+\frac{1}{2}=0$, and $4 y+4 z+1=0$. This system of equations give $(y, z)=(1 / 4,-1 / 2)$ or $(y, z)=(-1 / 2,1 / 4)$ as the desired equality cases.

Note: We can also prove (the weakened) Claim 2 by using Lagrange Multiplier, as follows. We first prove that, in fact, $x, y, z \in[-0.5,0.5]$. This can be proved by considering that

$$

-2 x+\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}\right)=(a-c)^{2}+(b-d)^{2} \geq 0

$$

We will prove the Claim 2, only that in this case, $x, y, z \in[-0.5,0.5]$. This is already sufficient to prove the original question. We already have the bounded domain $[-0.5,0.5]^{3}$, so the global minimum must occur somewhere. Thus, it suffices to consider two cases:

- If the global minimum lies on the boundary of $[-0.5,0.5]^{3}$. Then, one of $x, y, z$ must be -0.5 or 0.5 . By symmetry between $y$ and $z$, we split to a few more cases.

- If $x=0.5$, then $y=z=-0.5$, so $(x-y)(x-z)=1$, not the minimum.

- If $x=-0.5$, then both $y$ and $z$ must be greater or equal to $x$, so $(x-y)(x-z) \geq 0$, not the minimum.

- If $y=0.5$, then $x=z=-0.5$, so $(x-y)(x-z)=0$, not the minimum.

- If $y=-0.5$, then $z=-x$, so

$$

(x-y)(x-z)=2 x(x+0.5)

$$

which obtain the minimum at $x=-1 / 4$. This gives the desired equality case.

- If the global minimum lies in the interior $(-0.5,0.5)^{3}$, then we apply Lagrange multiplier:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x-y)(x-z)=\lambda \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x+y+z) \\

& \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x-y)(x-z)=\lambda \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x+y+z) \\

& \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(x-y)(x-z) \Longrightarrow z-x=\lambda \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(x+y+z) \\

& \Longrightarrow y-x=\lambda .

\end{aligned}

$$

Adding the last two equations gives $\lambda=0$, or $x=y=z$. This gives $(x-y)(x-z)=0$, not the minimum.

Having exhausted all cases, we are done.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 5.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2022_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 5"

}

| 77

| 1,440

|

2023

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n \geq 5$ be an integer. Consider $n$ squares with side lengths $1,2, \ldots, n$, respectively. The squares are arranged in the plane with their sides parallel to the $x$ and $y$ axes. Suppose that no two squares touch, except possibly at their vertices.

Show that it is possible to arrange these squares in a way such that every square touches exactly two other squares.

|

Set aside the squares with sidelengths $n-3, n-2, n-1$, and $n$ and suppose we can split the remaining squares into two sets $A$ and $B$ such that the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $A$ is 1 or 2 units larger than the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $B$.

String the squares of each set $A, B$ along two parallel diagonals, one for each diagonal. Now use the four largest squares along two perpendicular diagonals to finish the construction: one will have sidelengths $n$ and $n-3$, and the other, sidelengths $n-1$ and $n-2$. If the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $A$ is 1 unit larger than the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $B$, attach the squares with sidelengths $n-3$ and $n-1$ to the $A$-diagonal, and the other two squares to the $B$-diagonal. The resulting configuration, in which the $A$ and $B$-diagonals are represented by unit squares, and the sidelengths $a_{i}$ of squares from $A$ and $b_{j}$ of squares from $B$ are indicated within each square, follows:

Since $\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}\right) \sqrt{2}+\frac{((n-3)+(n-2)) \sqrt{2}}{2}=\left(b_{1}+b_{2}+\cdots+b_{\ell}+2\right) \sqrt{2}+\frac{(n+(n-1)) \sqrt{2}}{2}$, this case is done.

If the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $A$ is 1 unit larger than the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $B$, attach the squares with sidelengths $n-3$ and $n-2$ to the $A$-diagonal, and the other two squares to the $B$-diagonal. The resulting configuration follows:

Since $\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}\right) \sqrt{2}+\frac{((n-3)+(n-1)) \sqrt{2}}{2}=\left(b_{1}+b_{2}+\cdots+b_{\ell}+1\right) \sqrt{2}+\frac{(n+(n-2)) \sqrt{2}}{2}$, this case is also done.

In both cases, the distance between the $A$-diagonal and the $B$-diagonal is $\frac{((n-3)+n) \sqrt{2}}{2}=\frac{(2 n-3) \sqrt{2}}{2}$. Since $a_{i}, b_{j} \leq n-4, \frac{\left(a_{i}+b_{j}\right) \sqrt{2}}{2}<\frac{(2 n-4) \sqrt{2}}{2}<\frac{(2 n-3) \sqrt{2}}{2}$, and therefore the $A$ - and $B$-diagonals do not overlap.

Finally, we prove that it is possible to split the squares of sidelengths 1 to $n-4$ into two sets $A$ and $B$ such that the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $A$ is 1 or 2 units larger than the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $B$. One can do that in several ways; we present two possibilities:

- Direct construction: Split the numbers from 1 to $n-4$ into several sets of four consecutive numbers $\{t, t+1, t+2, t+3\}$, beginning with the largest numbers; put squares of sidelengths $t$ and $t+3$ in $A$ and squares of sidelengths $t+1$ and $t+2$ in $B$. Notice that $t+(t+3)=$ $(t+1)+(t+2)$. In the end, at most four numbers remain.

- If only 1 remains, put the corresponding square in $A$, so the sum of the sidelengths of the squares in $A$ is one unit larger that those in $B$;

- If 1 and 2 remains, put the square of sidelength 2 in $A$ and the square of sidelength 1 in $B$ (the difference is 1 );

- If 1,2 , and 3 remains, put the squares of sidelengths 1 and 3 in $A$, and the square of sidelength 2 in $B$ (the difference is 2 );

- If $1,2,3$, and 4 remains, put the squares of sidelengths 2 and 4 in $A$, and the squares of sidelengths 1 and 3 in $B$ (the difference is 2 ).

- Indirect construction: Starting with $A$ and $B$ as empty sets, add the squares of sidelengths $n-4, n-3, \ldots, 2$ to either $A$ or $B$ in that order such that at each stage the difference between the sum of the sidelengths in $A$ and the sum of the sidelengths of B is minimized. By induction it is clear that after adding an integer $j$ to one of the sets, this difference is at most $j$. In particular, the difference is 0,1 or 2 at the end. Finally adding the final 1 to one of the sets can ensure that the final difference is 1 or 2 . If necessary, flip $A$ and $B$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 91

| 1,266

|

2023

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Find all integers $n$ satisfying $n \geq 2$ and $\frac{\sigma(n)}{p(n)-1}=n$, in which $\sigma(n)$ denotes the sum of all positive divisors of $n$, and $p(n)$ denotes the largest prime divisor of $n$.

Answer: $n=6$.

|

Let $n=p_{1}^{\alpha_{1}} \cdot \ldots \cdot p_{k}^{\alpha_{k}}$ be the prime factorization of $n$ with $p_{1}<\ldots<p_{k}$, so that $p(n)=p_{k}$ and $\sigma(n)=\left(1+p_{1}+\cdots+p_{1}^{\alpha_{1}}\right) \ldots\left(1+p_{k}+\cdots+p_{k}^{\alpha_{k}}\right)$. Hence

$p_{k}-1=\frac{\sigma(n)}{n}=\prod_{i=1}^{k}\left(1+\frac{1}{p_{i}}+\cdots+\frac{1}{p_{i}^{\alpha_{i}}}\right)<\prod_{i=1}^{k} \frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{p_{i}}}=\prod_{i=1}^{k}\left(1+\frac{1}{p_{i}-1}\right) \leq \prod_{i=1}^{k}\left(1+\frac{1}{i}\right)=k+1$,

that is, $p_{k}-1<k+1$, which is impossible for $k \geq 3$, because in this case $p_{k}-1 \geq 2 k-2 \geq k+1$. Then $k \leq 2$ and $p_{k}<k+2 \leq 4$, which implies $p_{k} \leq 3$.

If $k=1$ then $n=p^{\alpha}$ and $\sigma(n)=1+p+\cdots+p^{\alpha}$, and in this case $n \nmid \sigma(n)$, which is not possible. Thus $k=2$, and $n=2^{\alpha} 3^{\beta}$ with $\alpha, \beta>0$. If $\alpha>1$ or $\beta>1$,

$$

\frac{\sigma(n)}{n}>\left(1+\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(1+\frac{1}{3}\right)=2 .

$$

Therefore $\alpha=\beta=1$ and the only answer is $n=6$.

Comment: There are other ways to deal with the case $n=2^{\alpha} 3^{\beta}$. For instance, we have $2^{\alpha+2} 3^{\beta}=\left(2^{\alpha+1}-1\right)\left(3^{\beta+1}-1\right)$. Since $2^{\alpha+1}-1$ is not divisible by 2 , and $3^{\beta+1}-1$ is not divisible by 3 , we have

$$

\left\{\begin{array} { l }

{ 2 ^ { \alpha + 1 } - 1 = 3 ^ { \beta } } \\

{ 3 ^ { \beta + 1 } - 1 = 2 ^ { \alpha + 2 } }

\end{array} \Longleftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array} { c }

{ 2 ^ { \alpha + 1 } - 1 = 3 ^ { \beta } } \\

{ 3 \cdot ( 2 ^ { \alpha + 1 } - 1 ) - 1 = 2 \cdot 2 ^ { \alpha + 1 } }

\end{array} \Longleftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{r}

2^{\alpha+1}=4 \\

3^{\beta}=3

\end{array}\right.\right.\right.

$$

and $n=2^{\alpha} 3^{\beta}=6$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 70

| 823

|

2023

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $A B C D$ be a parallelogram. Let $W, X, Y$, and $Z$ be points on sides $A B, B C, C D$, and $D A$, respectively, such that the incenters of triangles $A W Z, B X W, C Y X$ and $D Z Y$ form a parallelogram. Prove that $W X Y Z$ is a parallelogram.

|

Let the four incenters be $I_{1}, I_{2}, I_{3}$, and $I_{4}$ with inradii $r_{1}, r_{2}, r_{3}$, and $r_{4}$ respectively (in the order given in the question). Without loss of generality, let $I_{1}$ be closer to $A B$ than $I_{2}$. Let the acute angle between $I_{1} I_{2}$ and $A B$ (and hence also the angle between $I_{3} I_{4}$ and $C D$ ) be $\theta$. Then

$$

r_{2}-r_{1}=I_{1} I_{2} \sin \theta=I_{3} I_{4} \sin \theta=r_{4}-r_{3}

$$

which implies $r_{1}+r_{4}=r_{2}+r_{3}$. Similar arguments show that $r_{1}+r_{2}=r_{3}+r_{4}$. Thus we obtain $r_{1}=r_{3}$ and $r_{2}=r_{4}$.

Now let's consider the possible positions of $W, X, Y, Z$. Suppose $A Z \neq C X$. Without loss of generality assume $A Z>C X$. Since the incircles of $A W Z$ and $C Y X$ are symmetric about the centre of the parallelogram $A B C D$, this implies $C Y>A W$. Using similar arguments, we have

$$

C Y>A W \Longrightarrow B W>D Y \Longrightarrow D Z>B X \Longrightarrow C X>A Z

$$

which is a contradiction. Therefore $A Z=C X \Longrightarrow A W=C Y$ and $W X Y Z$ is a parallelogram.

Comment: There are several ways to prove that $r_{1}=r_{3}$ and $r_{2}=r_{4}$. The proposer shows the following three alternative approaches:

Using parallel lines: Let $O$ be the centre of parallelogram $A B C D$ and $P$ be the centre of parallelogram $I_{1} I_{2} I_{3} I_{4}$. Since $A I_{1}$ and $C I_{3}$ are angle bisectors, we must have $A I_{1} \| C I_{3}$. Let $\ell_{1}$ be the line through $O$ parallel to $A I_{1}$. Since $A O=O C, \ell_{1}$ is halfway between $A I_{1}$ and $C I_{3}$. Hence $P$ must lie on $\ell_{1}$.

Similarly, $P$ must also lie on $\ell_{2}$, the line through $O$ parallel to $B I_{2}$. Thus $P$ is the intersection of $\ell_{1}$ and $\ell_{2}$, which must be $O$. So the four incentres and hence the four incircles must be symmetric about $O$, which implies $r_{1}=r_{3}$ and $r_{2}=r_{4}$.

Using a rotation: Let the bisectors of $\angle D A B$ and $\angle A B C$ meet at $X$ and the bisectors of $\angle B C D$ and $\angle C D A$ meet at $Y$. Then $I_{1}$ is on $A X, I_{2}$ is on $B X, I_{3}$ is on $C Y$, and $I_{4}$ is on $D Y$. Let $O$ be the centre of $A B C D$. Then a 180 degree rotation about $O$ takes $\triangle A X B$ to $\triangle C Y D$. Under the same transformation $I_{1} I_{2}$ is mapped to a parallel segment $I_{1}^{\prime} I_{2}^{\prime}$ with $I_{1}^{\prime}$ on $C Y$ and $I_{2}^{\prime}$ on $D Y$. Since $I_{1} I_{2} I_{3} I_{4}$ is a parallelogram, $I_{3} I_{4}=I_{1} I_{2}$ and $I_{3} I_{4} \| I_{1} I_{2}$. Hence $I_{1}^{\prime} I_{2}^{\prime}$ and $I_{3} I_{4}$ are parallel, equal length segments on sides $C Y, D Y$ and we conclude that $I_{1}^{\prime}=I_{3}, I_{2}^{\prime}=I_{4}$. Hence the centre of $I_{1} I_{2} I_{3} I_{4}$ is also $O$ and we establish that by rotational symmetry that $r_{1}=r_{3}$ and $r_{2}=r_{4}$.

Using congruent triangles: Let $A I_{1}$ and $B I_{2}$ intersect at $E$ and let $C I_{3}$ and $D I_{4}$ intersect at $F$. Note that $\triangle A B E$ and $\triangle C D F$ are congruent, since $A B=C D$ and corresponding pairs of angles are equal (equal opposite angles parallelogram $A B C D$ are each bisected).

Since $A I_{1} \| C I_{3}$ and $I_{1} I_{2} \| I_{4} I_{3}, \angle I_{2} I_{1} E=\angle I_{4} I_{3} F$. Similarly $\angle I_{1} I_{2} E=\angle I_{3} I_{4} F$. Furthermore $I_{1} I_{2}=I_{3} I_{4}$. Hence triangles $I_{2} I_{1} E$ and $I 4 I_{3} F$ are also congruent.

Hence $A B E I_{1} I_{2}$ and $D C F I_{3} I_{4}$ are congruent. Therefore, the perpendicular distance from $I_{1}$ to $A B$ equals the perpendicular distance from $I_{3}$ to $C D$, that is, $r_{1}=r_{3}$. Similarly $r_{2}=r_{4}$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 93

| 1,372

|

2023

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Let $c>0$ be a given positive real and $\mathbb{R}_{>0}$ be the set of all positive reals. Find all functions $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}_{>0}$ such that

$$

f((c+1) x+f(y))=f(x+2 y)+2 c x \quad \text { for all } x, y \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}

$$

Answer: $f(x)=2 x$ for all $x>0$.

|

We first prove that $f(x) \geq 2 x$ for all $x>0$. Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $f(y)<2 y$ for some positive $y$. Choose $x$ such that $f((c+1) x+f(y))$ and $f(x+2 y)$ cancel out, that is,

$$

(c+1) x+f(y)=x+2 y \Longleftrightarrow x=\frac{2 y-f(y)}{c}

$$

Notice that $x>0$ because $2 y-f(y)>0$. Then $2 c x=0$, which is not possible. This contradiction yields $f(y) \geq 2 y$ for all $y>0$.

Now suppose, again for the sake of contradiction, that $f(y)>2 y$ for some $y>0$. Define the following sequence: $a_{0}$ is an arbitrary real greater than $2 y$, and $f\left(a_{n}\right)=f\left(a_{n-1}\right)+2 c x$, so that

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{r}

(c+1) x+f(y)=a_{n} \\

x+2 y=a_{n-1}

\end{array} \Longleftrightarrow x=a_{n-1}-2 y \quad \text { and } \quad a_{n}=(c+1)\left(a_{n-1}-2 y\right)+f(y) .\right.

$$

If $x=a_{n-1}-2 y>0$ then $a_{n}>f(y)>2 y$, so inductively all the substitutions make sense.

For the sake of simplicity, let $b_{n}=a_{n}-2 y$, so $b_{n}=(c+1) b_{n-1}+f(y)-2 y \quad(*)$. Notice that $x=b_{n-1}$ in the former equation, so $f\left(a_{n}\right)=f\left(a_{n-1}\right)+2 c b_{n-1}$. Telescoping yields

$$

f\left(a_{n}\right)=f\left(a_{0}\right)+2 c \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} b_{i} .

$$

One can find $b_{n}$ from the recurrence equation $(*): b_{n}=\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)(c+1)^{n}-\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}$, and then

$$

\begin{aligned}

f\left(a_{n}\right) & =f\left(a_{0}\right)+2 c \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}\left(\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)(c+1)^{i}-\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right) \\

& =f\left(a_{0}\right)+2\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)\left((c+1)^{n}-1\right)-2 n(f(y)-2 y)

\end{aligned}

$$

Since $f\left(a_{n}\right) \geq 2 a_{n}=2 b_{n}+4 y$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

& f\left(a_{0}\right)+2\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)\left((c+1)^{n}-1\right)-2 n(f(y)-2 y) \geq 2 b_{n}+4 y \\

= & 2\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)(c+1)^{n}-2 \frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}

\end{aligned}

$$

which implies

$$

f\left(a_{0}\right)+2 \frac{f(y)-2 y}{c} \geq 2\left(b_{0}+\frac{f(y)-2 y}{c}\right)+2 n(f(y)-2 y)

$$

which is not true for sufficiently large $n$.

A contradiction is reached, and thus $f(y)=2 y$ for all $y>0$. It is immediate that this function satisfies the functional equation.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 121

| 951

|

2023

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

There are $n$ line segments on the plane, no three intersecting at a point, and each pair intersecting once in their respective interiors. Tony and his $2 n-1$ friends each stand at a distinct endpoint of a line segment. Tony wishes to send Christmas presents to each of his friends as follows:

First, he chooses an endpoint of each segment as a "sink". Then he places the present at the endpoint of the segment he is at. The present moves as follows:

- If it is on a line segment, it moves towards the sink.

- When it reaches an intersection of two segments, it changes the line segment it travels on and starts moving towards the new sink.

If the present reaches an endpoint, the friend on that endpoint can receive their present. Prove Tony can send presents to exactly $n$ of his $2 n-1$ friends.

|

Draw a circle that encloses all the intersection points between line segments and extend all line segments until they meet the circle, and then move Tony and all his friends to the circle. Number the intersection points with the circle from 1 to $2 n$ anticlockwise, starting from Tony (Tony has number 1). We will prove that the friends eligible to receive presents are the ones on even-numbered intersection points.

First part: at most $n$ friends can receive a present.

The solution relies on a well-known result: the $n$ lines determine regions inside the circle; then it is possible to paint the regions with two colors such that no regions with a common (line) boundary have the same color. The proof is an induction on $n$ : the fact immediately holds for $n=0$, and the induction step consists on taking away one line $\ell$, painting the regions obtained with $n-1$ lines, drawing $\ell$ again and flipping all colors on exactly one half plane determined by $\ell$.

Now consider the line starting on point 1. Color the regions in red and blue such that neighboring regions have different colors, and such that the two regions that have point 1 as a vertex are red on the right and blue on the left, from Tony's point of view. Finally, assign to each red region the clockwise direction and to each blue region the anticlockwise direction. Because of the coloring, every boundary will have two directions assigned, but the directions are the same since every boundary divides regions of different colors. Then the present will follow the directions assigned to the regions: it certainly does for both regions in the beginning, and when the present reaches an intersection it will keep bordering one of the two regions it was dividing. To finish this part of the problem, consider the regions that share a boundary with the circle. The directions alternate between outcoming and incoming, starting from 1 (outcoming), so all even-numbered vertices are directed as incoming and are the only ones able to receive presents. Second part: all even-numbered vertices can receive a present.

First notice that, since every two chords intersect, every chord separates the endpoints of each of the other $n-1$ chords. Therefore, there are $n-1$ vertices on each side of every chord, and each chord connects vertices $k$ and $k+n, 1 \leq k \leq n$.

We prove a stronger result by induction in $n$ : let $k$ be an integer, $1 \leq k \leq n$. Direct each chord from $i$ to $i+n$ if $1 \leq i \leq k$ and from $i+n$ to $i$ otherwise; in other words, the sinks are $k+1, k+2, \ldots, k+n$. Now suppose that each chord sends a present, starting from the vertex opposite to each sink, and all presents move with the same rules. Then $k-i$ sends a present to $k+i+1, i=0,1, \ldots, n-1$ (indices taken modulo $2 n$ ). In particular, for $i=k-1$, Tony, in vertex 1 , send a present to vertex $2 k$. Also, the $n$ paths the presents make do not cross (but they may touch.) More formally, for all $i, 1 \leq i \leq n$, if one path takes a present from $k-i$ to $k+i+1$, separating the circle into two regions, all paths taking a present from $k-j$ to $k+j+1, j<i$, are completely contained in one region, and all paths taking a present from

$k-j$ to $k+j+1, j>i$, are completely contained in the other region. For instance, possible ${ }^{1}$ paths for $k=3$ and $n=5$ follow:

The result is true for $n=1$. Let $n>1$ and assume the result is true for less chords. Consider the chord that takes $k$ to $k+n$ and remove it. Apply the induction hypothesis to the remaining $n-1$ lines: after relabeling, presents would go from $k-i$ to $k+i+2,1 \leq i \leq n-1$ if the chord were not there.

Reintroduce the chord that takes $k$ to $k+n$. From the induction hypothesis, the chord intersects the paths of the presents in the following order: the $i$-th path the chord intersects is the the one that takes $k-i$ to $k+i, i=1,2, \ldots, n-1$.

Paths without chord $k \rightarrow k+n$

Corrected paths with chord $k \rightarrow k+n$

Then the presents cover the following new paths: the present from $k$ will leave its chord and take the path towards $k+1$; then, for $i=1,2, \ldots, n-1$, the present from $k-i$ will meet the chord from $k$ to $k+n$, move towards the intersection with the path towards $k+i+1$ and go to $k+i+1$, as desired. Notice that the paths still do not cross. The induction (and the solution) is now complete.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 179

| 1,127

|

2023

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

There are $n$ line segments on the plane, no three intersecting at a point, and each pair intersecting once in their respective interiors. Tony and his $2 n-1$ friends each stand at a distinct endpoint of a line segment. Tony wishes to send Christmas presents to each of his friends as follows:

First, he chooses an endpoint of each segment as a "sink". Then he places the present at the endpoint of the segment he is at. The present moves as follows:

- If it is on a line segment, it moves towards the sink.

- When it reaches an intersection of two segments, it changes the line segment it travels on and starts moving towards the new sink.

If the present reaches an endpoint, the friend on that endpoint can receive their present. Prove Tony can send presents to exactly $n$ of his $2 n-1$ friends.

|

First part: at most n friends can receive a present.

Similarly to the first solution, consider a circle that encompasses all line segments, extend the lines, and use the endpoints of the chords instead of the line segments, and prove that each chord connects vertices $k$ and $k+n$. We also consider, even in the first part, $n$ presents leaving from $n$ outcoming vertices.

First we prove that a present always goes to a sink. If it does not, then it loops; let it first enter the loop at point $P$ after turning from chord $a$ to chord $b$. Therefore after it loops once,

[^0]it must turn to chord $b$ at $P$. But $P$ is the intersection of $a$ and $b$, so the present should turn from chord $a$ to chord $b$, which can only be done in one way - the same way it came in first. This means that some part of chord $a$ before the present enters the loop at $P$ is part of the loop, which contradicts the fact that $P$ is the first point in the loop. So no present enters a loop, and every present goes to a sink.

There are no loops

No two paths cross

The present paths also do not cross: in fact, every time two paths share a point $P$, intersection of chords $a$ and $b$, one path comes from $a$ to $b$ and the other path comes from $b$ to $a$, and they touch at $P$. This implies the following sequence of facts:

- Every path divides the circle into two regions with paths connecting vertices within each region.

- All $n$ presents will be delivered to $n$ different persons; that is, all sinks receive a present. This implies that every vertex is an endpoint of a path.

- The number of chord endpoints inside each region is even, because they are connected within their own region.

Now consider the path starting at vertex 1 , with Tony. It divides the circle into two regions with an even number of vertices in their interior. Then there is an even number of vertices between Tony and the recipient of his present, that is, their vertex is an even numbered one. Second part: all even-numbered vertices can receive a present.

The construction is the same as the in the previous solution: direct each chord from $i$ to $i+n$ if $1 \leq i \leq k$ and from $i+n$ to $i$ otherwise; in other words, the sinks are $k+1, k+2, \ldots, k+n$. Then, since the paths do not cross, $k$ will send a present to $k+1, k-1$ will send a present to $k+2$, and so on, until 1 sends a present to $(k+1)+(k-1)=2 k$.

[^0]: ${ }^{1}$ The paths do not depend uniquely on $k$ and $n$; different chord configurations and vertex labelings may change the paths.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2023_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2"

}

| 179

| 644

|

2024

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Consider a $100 \times 100$ table, and identify the cell in row $a$ and column $b, 1 \leq a, b \leq 100$, with the ordered pair $(a, b)$. Let $k$ be an integer such that $51 \leq k \leq 99$. A $k$-knight is a piece that moves one cell vertically or horizontally and $k$ cells to the other direction; that is, it moves from $(a, b)$ to $(c, d)$ such that $(|a-c|,|b-d|)$ is either $(1, k)$ or $(k, 1)$. The $k$-knight starts at cell $(1,1)$, and performs several moves. A sequence of moves is a sequence of cells $\left(x_{0}, y_{0}\right)=(1,1)$, $\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right),\left(x_{2}, y_{2}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{n}, y_{n}\right)$ such that, for all $i=1,2, \ldots, n, 1 \leq x_{i}, y_{i} \leq 100$ and the $k$-knight can move from $\left(x_{i-1}, y_{i-1}\right)$ to $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right)$. In this case, each cell $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right)$ is said to be reachable. For each $k$, find $L(k)$, the number of reachable cells.

Answer: $L(k)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}100^{2}-(2 k-100)^{2} & \text { if } k \text { is even } \\ \frac{100^{2}-(2 k-100)^{2}}{2} & \text { if } k \text { is odd }\end{array}\right.$.

|

Cell $(x, y)$ is directly reachable from another cell if and only if $x-k \geq 1$ or $x+k \leq 100$ or $y-k \geq 1$ or $y+k \leq 100$, that is, $x \geq k+1$ or $x \leq 100-k$ or $y \geq k+1$ or $y \leq 100-k(*)$. Therefore the cells $(x, y)$ for which $101-k \leq x \leq k$ and $101-k \leq y \leq k$ are unreachable. Let $S$ be this set of unreachable cells in this square, namely the square of cells $(x, y), 101-k \leq x, y \leq k$. If condition $(*)$ is valid for both $(x, y)$ and $(x \pm 2, y \pm 2)$ then one can move from $(x, y)$ to $(x \pm 2, y \pm 2)$, if they are both in the table, with two moves: either $x \leq 50$ or $x \geq 51$; the same is true for $y$. In the first case, move $(x, y) \rightarrow(x+k, y \pm 1) \rightarrow(x, y \pm 2)$ or $(x, y) \rightarrow$ $(x \pm 1, y+k) \rightarrow(x \pm 2, y)$. In the second case, move $(x, y) \rightarrow(x-k, y \pm 1) \rightarrow(x, y \pm 2)$ or $(x, y) \rightarrow(x \pm 1, y-k) \rightarrow(x \pm 2, y)$.

Hence if the table is colored in two colors like a chessboard, if $k \leq 50$, cells with the same color as $(1,1)$ are reachable. Moreover, if $k$ is even, every other move changes the color of the occupied cell, and all cells are potentially reachable; otherwise, only cells with the same color as $(1,1)$ can be visited. Therefore, if $k$ is even then the reachable cells consists of all cells except the center square defined by $101-k \leq x \leq k$ and $101-k \leq y \leq k$, that is, $L(k)=100^{2}-(2 k-100)^{2}$; if $k$ is odd, then only half of the cells are reachable: the ones with the same color as $(1,1)$, and $L(k)=\frac{1}{2}\left(100^{2}-(2 k-100)^{2}\right)$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2024_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 446

| 627

|

2024

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer and $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be positive real numbers. Prove that

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{2^{i}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{i}}\right)^{2^{i}} \geq \frac{2}{1+a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}}-\frac{1}{2^{n}}

$$

|

We first prove the following lemma:

Lemma 1. For $k$ positive integer and $x, y>0$,

$$

\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k}}+\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k}} \geq 2\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)^{2^{k-1}}

$$

The proof goes by induction. For $k=1$, we have

$$

\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2} \geq 2\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)

$$

which reduces to

$$

x y(x-y)^{2}+(x y-1)^{2} \geq 0 .

$$

For $k>1$, by the inequality $2\left(A^{2}+B^{2}\right) \geq(A+B)^{2}$ applied at $A=\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k-1}}$ and $B=\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k-1}}$ followed by the induction hypothesis

$$

\begin{aligned}

2\left(\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k}}+\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k}}\right) & \geq\left(\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k-1}}+\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k-1}}\right)^{2} \\

& \geq\left(2\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)^{2^{k-2}}\right)^{2}=4\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)^{2^{k-1}}

\end{aligned}

$$

from which the lemma follows.

The problem now can be deduced from summing the following applications of the lemma, multiplied by the appropriate factor:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{2^{n}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n}}+\frac{1}{2^{n}}\left(\frac{2}{1+1}\right)^{2^{n}} & \geq \frac{1}{2^{n-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n} \cdot 1}\right)^{2^{n-1}} \\

\frac{1}{2^{n-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-1}}\right)^{2^{n-1}}+\frac{1}{2^{n-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n-1}} & \geq \frac{1}{2^{n-2}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n-2}} \\

\frac{1}{2^{n-2}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-2}}\right)^{2^{n-2}}+\frac{1}{2^{n-2}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n-2}} & \geq \frac{1}{2^{n-3}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-2} a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n-3}} \\

\ldots & )^{2^{k}} \\

\frac{1}{2^{k}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{k}}\right)^{2^{k}}+\frac{1}{2^{k}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{k+1} \ldots a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2^{k-1}} & \geq \frac{1}{2^{k-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{k} \ldots a_{n-2} a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2} \\

\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{1}}\right)^{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{2} \ldots a_{n-1} a_{n}}\right)^{2} & \geq \frac{2}{1+a_{1} \ldots a_{n-2} a_{n-1} a_{n}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Comment: Equality occurs if and only if $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}=1$.

Comment: The main motivation for the lemma is trying to "telescope" the sum

$$

\frac{1}{2^{n}}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{2^{i}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{i}}\right)^{2^{i}}

$$

that is,

$$

\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{1}}\right)^{2}+\cdots+\frac{1}{2^{n-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n-1}}\right)^{2^{n-1}}+\frac{1}{2^{n}}\left(\frac{2}{1+a_{n}}\right)^{2^{n}}+\frac{1}{2^{n}}\left(\frac{2}{1+1}\right)^{2^{n}}

$$

to obtain an expression larger than or equal to

$$

\frac{2}{1+a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}}

$$

It seems reasonable to obtain a inequality that can be applied from right to left, decreases the exponent of the factor $1 / 2^{k}$ by 1 , and multiplies the variables in the denominator. Given that, the lemma is quite natural:

$$

\frac{1}{2^{k}}\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k}}+\frac{1}{2^{k}}\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k}} \geq \frac{1}{2^{k-1}}\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)^{2^{i-1}}

$$

or

$$

\left(\frac{2}{1+x}\right)^{2^{k}}+\left(\frac{2}{1+y}\right)^{2^{k}} \geq 2\left(\frac{2}{1+x y}\right)^{2^{k-1}}

$$

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2024_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 110

| 1,506

|

2024

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Prove that for every positive integer $t$ there is a unique permutation $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{t-1}$ of $0,1, \ldots, t-$ 1 such that, for every $0 \leq i \leq t-1$, the binomial coefficient $\binom{t+i}{2 a_{i}}$ is odd and $2 a_{i} \neq t+i$.

|

We constantly make use of Kummer's theorem which, in particular, implies that $\binom{n}{k}$ is odd if and only if $k$ and $n-k$ have ones in different positions in binary. In other words, if $S(x)$ is the set of positions of the digits 1 of $x$ in binary (in which the digit multiplied by $2^{i}$ is in position $i),\binom{n}{k}$ is odd if and only if $S(k) \subseteq S(n)$. Moreover, if we set $k<n, S(k)$ is a proper subset of $S(n)$, that is, $|S(k)|<|S(n)|$.

We start with a lemma that guides us how the permutation should be set.

## Lemma 1.

$$

\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(t+i)|=t+\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(2 i)|

$$

The proof is just realizing that $S(2 i)=\{1+x, x \in S(i)\}$ and $S(2 i+1)=\{0\} \cup\{1+x, x \in S(i)\}$, because $2 i$ in binary is $i$ followed by a zero and $2 i+1$ in binary is $i$ followed by a one. Therefore

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(t+i)| & =\sum_{i=0}^{2 t-1}|S(i)|-\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(i)|=\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(2 i)|+\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(2 i+1)|-\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(i)| \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(i)|+\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}(1+|S(i)|)-\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(i)|=t+\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(i)|=t+\sum_{i=0}^{t-1}|S(2 i)|

\end{aligned}

$$

The lemma has an immediate corollary: since $t+i>2 a_{i}$ and $\binom{t+i}{2 a_{i}}$ is odd for all $i, 0 \leq i \leq t-1$, $S\left(2 a_{i}\right) \subset S(t+i)$ with $\left|S\left(2 a_{i}\right)\right| \leq|S(t+i)|-1$. Since the sum of $\left|S\left(2 a_{i}\right)\right|$ is $t$ less than the sum of $|S(t+i)|$, and there are $t$ values of $i$, equality must occur, that is, $\left|S\left(2 a_{i}\right)\right|=|S(t+i)|-1$, which in conjunction with $S\left(2 a_{i}\right) \subset S(t+i)$ means that $t+i-2 a_{i}=2^{k_{i}}$ for every $i, 0 \leq i \leq t-1$, $k_{i} \in S(t+i)$ (more precisely, $\left\{k_{i}\right\}=S(t+i) \backslash S\left(2 a_{i}\right)$.)