year

stringdate 1961-01-01 00:00:00

2025-01-01 00:00:00

⌀ | tier

stringclasses 5

values | problem_label

stringclasses 119

values | problem_type

stringclasses 13

values | exam

stringclasses 28

values | problem

stringlengths 87

2.77k

| solution

stringlengths 834

13k

| metadata

dict | problem_tokens

int64 50

903

| solution_tokens

int64 500

3.93k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1989

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Prove that the equation

$$

6\left(6 a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}\right)=5 n^{2}

$$

has no solutions in integers except $a=b=c=n=0$.

|

We can suppose without loss of generality that $a, b, c, n \geq 0$. Let $(a, b, c, n)$ be a solution with minimum sum $a+b+c+n$. Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $a+b+c+n>0$. Since 6 divides $5 n^{2}, n$ is a multiple of 6 . Let $n=6 n_{0}$. Then the equation reduces to

$$

6 a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}=30 n_{0}^{2}

$$

The number $c$ is a multiple of 3 , so let $c=3 c_{0}$. The equation now reduces to

$$

2 a^{2}+b^{2}+3 c_{0}^{2}=10 n_{0}^{2}

$$

Now look at the equation modulo 8:

$$

b^{2}+3 c_{0}^{2} \equiv 2\left(n_{0}^{2}-a^{2}\right) \quad(\bmod 8)

$$

Integers $b$ and $c_{0}$ have the same parity. Either way, since $x^{2}$ is congruent to 0 or 1 modulo 4 , $b^{2}+3 c_{0}^{2}$ is a multiple of 4 , so $n_{0}^{2}-a^{2}=\left(n_{0}-a\right)\left(n_{0}+a\right)$ is even, and therefore also a multiple of 4 , since $n_{0}-a$ and $n_{0}+a$ have the same parity. Hence $2\left(n_{0}^{2}-a^{2}\right)$ is a multiple of 8 , and

$$

b^{2}+3 c_{0}^{2} \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 8)

$$

If $b$ and $c_{0}$ are both odd, $b^{2}+3 c_{0}^{2} \equiv 4(\bmod 8)$, which is impossible. Then $b$ and $c_{0}$ are both even. Let $b=2 b_{0}$ and $c_{0}=2 c_{1}$, and we find

$$

a^{2}+2 b_{0}^{2}+6 c_{1}^{2}=5 n_{0}^{2}

$$

Look at the last equation modulo 8:

$$

a^{2}+3 n_{0}^{2} \equiv 2\left(c_{1}^{2}-b_{0}^{2}\right) \quad(\bmod 8)

$$

A similar argument shows that $a$ and $n_{0}$ are both even.

We have proven that $a, b, c, n$ are all even. Then, dividing the original equation by 4 we find

$$

6\left(6(a / 2)^{2}+3(b / 2)^{2}+(c / 2)^{2}\right)=5(n / 2)^{2}

$$

and we find that $(a / 2, b / 2, c / 2, n / 2)$ is a new solution with smaller sum. This is a contradiction, and the only solution is $(a, b, c, n)=(0,0,0,0)$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1989_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 51

| 749

|

1989

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3}$ be three points in the plane, and for convenience,let $A_{4}=A_{1}, A_{5}=A_{2}$. For $n=1,2$, and 3 , suppose that $B_{n}$ is the midpoint of $A_{n} A_{n+1}$, and suppose that $C_{n}$ is the midpoint of $A_{n} B_{n}$. Suppose that $A_{n} C_{n+1}$ and $B_{n} A_{n+2}$ meet at $D_{n}$, and that $A_{n} B_{n+1}$ and $C_{n} A_{n+2}$ meet at $E_{n}$. Calculate the ratio of the area of triangle $D_{1} D_{2} D_{3}$ to the area of triangle $E_{1} E_{2} E_{3}$.

Answer: $\frac{25}{49}$.

|

Let $G$ be the centroid of triangle $A B C$, and also the intersection point of $A_{1} B_{2}, A_{2} B_{3}$, and $A_{3} B_{1}$ 。

By Menelao's theorem on triangle $B_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$ and line $A_{1} D_{1} C_{2}$,

$$

\frac{A_{1} B_{1}}{A_{1} A_{2}} \cdot \frac{D_{1} A_{3}}{D_{1} B_{1}} \cdot \frac{C_{2} A_{2}}{C_{2} A_{3}}=1 \Longleftrightarrow \frac{D_{1} A_{3}}{D_{1} B_{1}}=2 \cdot 3=6 \Longleftrightarrow \frac{D_{1} B_{1}}{A_{3} B_{1}}=\frac{1}{7}

$$

Since $A_{3} G=\frac{2}{3} A_{3} B_{1}$, if $A_{3} B_{1}=21 t$ then $G A_{3}=14 t, D_{1} B_{1}=\frac{21 t}{7}=3 t, A_{3} D_{1}=18 t$, and $G D_{1}=A_{3} D_{1}-A_{3} G=18 t-14 t=4 t$, and

$$

\frac{G D_{1}}{G A_{3}}=\frac{4}{14}=\frac{2}{7}

$$

Similar results hold for the other medians, therefore $D_{1} D_{2} D_{3}$ and $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$ are homothetic with center $G$ and ratio $-\frac{2}{7}$.

By Menelao's theorem on triangle $A_{1} A_{2} B_{2}$ and line $C_{1} E_{1} A_{3}$,

$$

\frac{C_{1} A_{1}}{C_{1} A_{2}} \cdot \frac{E_{1} B_{2}}{E_{1} A_{1}} \cdot \frac{A_{3} A_{2}}{A_{3} B_{2}}=1 \Longleftrightarrow \frac{E_{1} B_{2}}{E_{1} A_{1}}=3 \cdot \frac{1}{2}=\frac{3}{2} \Longleftrightarrow \frac{A_{1} E_{1}}{A_{1} B_{2}}=\frac{2}{5}

$$

If $A_{1} B_{2}=15 u$, then $A_{1} G=\frac{2}{3} \cdot 15 u=10 u$ and $G E_{1}=A_{1} G-A_{1} E_{1}=10 u-\frac{2}{5} \cdot 15 u=4 u$, and

$$

\frac{G E_{1}}{G A_{1}}=\frac{4}{10}=\frac{2}{5}

$$

Similar results hold for the other medians, therefore $E_{1} E_{2} E_{3}$ and $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$ are homothetic with center $G$ and ratio $\frac{2}{5}$.

Then $D_{1} D_{2} D_{3}$ and $E_{1} E_{2} E_{3}$ are homothetic with center $G$ and ratio $-\frac{2}{7}: \frac{2}{5}=-\frac{5}{7}$, and the ratio of their area is $\left(\frac{5}{7}\right)^{2}=\frac{25}{49}$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1989_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution\n"

}

| 219

| 864

|

1989

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Let $S$ be a set consisting of $m$ pairs $(a, b)$ of positive integers with the property that $1 \leq a<$ $b \leq n$. Show that there are at least

$$

4 m \frac{\left(m-\frac{n^{2}}{4}\right)}{3 n}

$$

triples $(a, b, c)$ such that $(a, b),(a, c)$, and $(b, c)$ belong to $S$.

|

Call a triple $(a, b, c)$ good if and only if $(a, b),(a, c)$, and $(b, c)$ all belong to $S$. For $i$ in $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$, let $d_{i}$ be the number of pairs in $S$ that contain $i$, and let $D_{i}$ be the set of numbers paired with $i$ in $S$ (so $\left|D_{i}\right|=d_{i}$ ). Consider a pair $(i, j) \in S$. Our goal is to estimate the number of integers $k$ such that any permutation of $\{i, j, k\}$ is good, that is, $\left|D_{i} \cap D_{j}\right|$. Note that $i \notin D_{i}$ and $j \notin D_{j}$, so $i, j \notin D_{i} \cap D_{j}$; thus any $k \in D_{i} \cap D_{j}$ is different from both $i$ and $j$, and $\{i, j, k\}$ has three elements as required. Now, since $D_{i} \cup D_{j} \subseteq\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$,

$$

\left|D_{i} \cap D_{j}\right|=\left|D_{i}\right|+\left|D_{j}\right|-\left|D_{i} \cup D_{j}\right| \leq d_{i}+d_{j}-n

$$

Summing all the results, and having in mind that each good triple is counted three times (one for each two of the three numbers), the number of good triples $T$ is at least

$$

T \geq \frac{1}{3} \sum_{(i, j) \in S}\left(d_{i}+d_{j}-n\right)

$$

Each term $d_{i}$ appears each time $i$ is in a pair from $S$, that is, $d_{i}$ times; there are $m$ pairs in $S$, so $n$ is subtracted $m$ times. By the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality

$$

T \geq \frac{1}{3}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}^{2}-m n\right) \geq \frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}\right)^{2}}{n}-m n\right) .

$$

Finally, the sum $\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}$ is $2 m$, since $d_{i}$ counts the number of pairs containing $i$, and each pair $(i, j)$ is counted twice: once in $d_{i}$ and once in $d_{j}$. Therefore

$$

T \geq \frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{(2 m)^{2}}{n}-m n\right)=4 m \frac{\left(m-\frac{n^{2}}{4}\right)}{3 n} .

$$

Comment: This is a celebrated graph theory fact named Goodman's bound, after A. M. Goodman's method published in 1959. The generalized version of the problem is still studied to this day.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1989_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 104

| 742

|

1989

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Determine all functions $f$ from the reals to the reals for which

(1) $f(x)$ is strictly increasing,

(2) $f(x)+g(x)=2 x$ for all real $x$, where $g(x)$ is the composition inverse function to $f(x)$.

(Note: $f$ and $g$ are said to be composition inverses if $f(g(x))=x$ and $g(f(x))=x$ for all real x.)

Answer: $f(x)=x+c, c \in \mathbb{R}$ constant.

|

Denote by $f_{n}$ the $n$th iterate of $f$, that is, $f_{n}(x)=\underbrace{f(f(\ldots f}_{n \text { times }}(x)))$.

Plug $x \rightarrow f_{n+1}(x)$ in (2): since $g\left(f_{n+1}(x)\right)=g\left(f\left(f_{n}(x)\right)\right)=f_{n}(x)$,

$$

f_{n+2}(x)+f_{n}(x)=2 f_{n+1}(x)

$$

that is,

$$

f_{n+2}(x)-f_{n+1}(x)=f_{n+1}(x)-f_{n}(x)

$$

Therefore $f_{n}(x)-f_{n-1}(x)$ does not depend on $n$, and is equal to $f(x)-x$. Summing the corresponding results for smaller values of $n$ we find

$$

f_{n}(x)-x=n(f(x)-x) .

$$

Since $g$ has the same properties as $f$,

$$

g_{n}(x)-x=n(g(x)-x)=-n(f(x)-x) .

$$

Finally, $g$ is also increasing, because since $f$ is increasing $g(x)>g(y) \Longrightarrow f(g(x))>$ $f(g(y)) \Longrightarrow x>y$. An induction proves that $f_{n}$ and $g_{n}$ are also increasing functions.

Let $x>y$ be real numbers. Since $f_{n}$ and $g_{n}$ are increasing,

$$

x+n(f(x)-x)>y+n(f(y)-y) \Longleftrightarrow n[(f(x)-x)-(f(y)-y)]>y-x

$$

and

$$

x-n(f(x)-x)>y-n(f(y)-y) \Longleftrightarrow n[(f(x)-x)-(f(y)-y)]<x-y

$$

Summing it up,

$$

|n[(f(x)-x)-(f(y)-y)]|<x-y \quad \text { for all } n \in \mathbb{Z}_{>0}

$$

Suppose that $a=f(x)-x$ and $b=f(y)-y$ are distinct. Then, for all positive integers $n$,

$$

|n(a-b)|<x-y

$$

which is false for a sufficiently large $n$. Hence $a=b$, and $f(x)-x$ is a constant $c$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$, that is, $f(x)=x+c$.

It is immediate that $f(x)=x+c$ satisfies the problem, as $g(x)=x-c$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1989_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 123

| 598

|

1990

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

In $\triangle A B C$, let $D, E, F$ be the midpoints of $B C, A C, A B$ respectively and let $G$ be the centroid of the triangle.

For each value of $\angle B A C$, how many non-similar triangles are there in which $A E G F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral?

|

Let $I$ be the intersection of $A G$ and $E F$.

Let $\delta=A I . I G-F I$ IE. Then

$$

A I=A D / 2, \quad I G=A D / 6, \quad F I=B C / 4=I E

$$

Further, applying the cosine rule to triangles $A B D, A C D$ we get

$$

\begin{aligned}

A B^{2} & =B C^{2} / 4+A D^{2}-A D \cdot B C \cdot \cos \angle B D A, \\

A C^{2} & =B C^{2} / 4+A D^{2}+A D \cdot B C \cdot \cos \angle B D A, \\

\text { so } \quad A D^{2} & =\left(A B^{2}+A C^{2}-B C^{2} / 2\right) / 2

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

\delta & =\left(A B^{2}+A C^{2}-2 B C^{2}\right) / 24 \\

& =\left(4 A B \cdot A C \cdot \cos \angle B A C-A B^{2}-A C^{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now $A E F G$ is a cyclic quadrilateral if and only if $\delta=0$, i.e. if and only if

$$

\begin{aligned}

\cos \angle B A C & =\left(A B^{2}+A B^{2}\right) /(4 \cdot A B \cdot A C) \\

& =(A B / A C+A C / A B) / 4

\end{aligned}

$$

5

Now $A B / A C+A C / A B \geq 2$. Hence $\cos \angle B A C \geq 1 / 2$ and so $\angle B A C \leq 60^{\circ}$.

For $\angle B A C>60^{\circ}$ there is no triangle with the required property.

For $\angle B A C=60^{\circ}$ there exists, within similarity, precisely one triangle (which is equilateral) having the required property.

For $\angle B A C<60^{\circ}$ there exists, within similarity, again precisely one triangle having the required property (even though for fixed median $A E$ there are two, but one arises from the other by interchanging point $B$ with point $C$, thus proving them to be similar).

|

{

"problem_match": "# Question 1 ",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1990_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# FIRST SOLUTION\n\n"

}

| 75

| 571

|

1990

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

In $\triangle A B C$, let $D, E, F$ be the midpoints of $B C, A C, A B$ respectively and let $G$ be the centroid of the triangle.

For each value of $\angle B A C$, how many non-similar triangles are there in which $A E G F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral?

|

in the figure as shown below, we first show that it is necessary that $\angle A$ is less than $90^{\circ}$ if the quadrilateral $A E G F$ ; cyclic.

Now, since $E F \| B C$, we get

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle E G F & =180^{\circ}-\left(B_{1}+C_{1}\right) \\

& \geq 180^{\circ}-(B+C) \\

& =A .

\end{aligned}

$$

(1)

Thus, if $A E G F$ is cyclic, we would have $\angle E G F+\angle A=180^{\circ}$. Therefore it is necessary that $0<\angle A \leq 90^{\circ}$.

## Continuation "A"

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of $\triangle A F E$. Without loss of generality, let the radius of this circle be 1.

We then let $A=1, F=z=e^{i \theta}$ and $E=z e^{2 i \alpha}=e^{i(\theta+2 \alpha)}$.

Then $\angle A=\alpha, 0<\alpha \leq 90^{\circ}$, and $0<\theta<360^{\circ}-2 \alpha$.

Thus,

$$

B=2 z-1

$$

and

$$

\begin{aligned}

G & =\frac{1}{3}(2 z-1)+\frac{2}{3}\left(z e^{2 i \alpha}\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{3}\left(2 e^{i \theta}+2 e^{i(\theta+2 \alpha)}-1\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

For quadrilateral $A F G E$ to be cyclic, it is now necessary that

$$

|G|=1 .

$$

For $|G|=1$, we must have

$$

\begin{aligned}

9= & (2 \cos (\theta)+2 \cos (\theta+2 \alpha)-1)^{2}+(2 \sin (\theta)+2 \sin (\theta+2 \alpha))^{2} \\

= & 4\left(\cos ^{2}(\theta)+\sin ^{2}(\theta)\right)+4\left(\cos ^{2}(\theta+2 \alpha)+\sin ^{2}(\theta+2 \alpha)\right)+1 \\

& +8(\cos (\theta) \cos (\theta+2 \alpha)+\sin (\theta) \sin (\theta+2 \alpha))-4 \cos (\theta)-4 \cos (\theta+2 \alpha) \\

= & 9+8 \cos (2 \alpha)-8 \cos (\alpha) \cos (\theta+\alpha)

\end{aligned}

$$

so that

$$

\cos (\theta+\alpha)=\frac{\cos (2 \alpha)}{\cos (\alpha)}

$$

] Now, $\left|\frac{\cos (2 \alpha)}{\cos (\alpha)}\right| \leq 1$ if and only if $\alpha \in\left(0,60^{\circ}\right]$ in the range of $\alpha$ under consideration, that is $\alpha \in\left(0,00^{\circ}\right]$. There is equality if and only if $\alpha=60^{\circ}$.

$\square$ Note there is only one solution. The apparent other solution is the mirror image of the first. We are solving for $\alpha+\theta$. The other solution is $360^{\circ}-\alpha-\theta$.

## Continuation "B"

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of triangle $A E F$. Let $A P$ be a diameter of this circle. Construct the circle with centre $P$ and radius $A P$. Then $B$ and $C$ lie on this circle.

It is clear that the problem is solved if we allow the angle $\angle B A C=\alpha$ to vary and restrict $B$ and $C$ to the constructed circle.

Let $\theta$ be the angle from the drawn axis. Then $\theta$ lies in the range $\left(0,180^{\circ}-\alpha\right)$. We must not forget the necessary restriction of $\alpha$, that is $\alpha \in\left(0,90^{\circ}\right.$.

Now, $D$ lies on an arc of a circle, centre $P$, radius $P D$ exterior to the circle, centre $O$, radius $A O$.

By similarity, $G$, lies on an arc of a circle, centre $Q$, radius $Q G$ where $A Q=\frac{2}{3} A P$ and $Q G=\frac{2}{3} P D$.

For the quadrilateral $A F G E$ to be cyclic, we must have that the radius $Q G$ is greater than or equal to $Q P$.

The easiest way to calulate these radii is to consider the case in which the diameter $A P$ bisects the angle $\angle B A C$.

Thus we re-draw the diagram as below. Let $A H$ be a diameter of the larger circle.

Thus we have $A H=4$ and by similar triangles,

$$

\frac{A D}{A B}=\frac{A B}{A H}=\cos \left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)

$$

so that

$$

\begin{aligned}

A D & =4 \cos ^{2}\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right) \\

& =2+2 \cos (\alpha) .

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus $P D=2 \cos (\alpha)$ and $Q G=\frac{2}{3} 2 \cos (\alpha)=\frac{4}{3} \cos (\alpha)$.

The necessary condition for a cyclic quadrilateral is then

$$

\frac{4}{3}(1+\cos (\alpha)) \geq 2

$$

[5

$$

\cos (\alpha) \geq \frac{1}{2}

$$

:7

Thus it is clear that there is precisely one (up to similarity) solution for $0<\alpha \leq 60^{\circ}$ and no solutions otherwise.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Question 1 ",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1990_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nTHIRD SOLUTION\n"

}

| 75

| 1,379

|

1990

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be positive real numbers, and let $S_{k}$ be the sum of products of $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ taken $k$ at a time.

Show that

$$

S_{k} S_{n-k} \geq\binom{ n}{k}^{2} a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}, \quad \text { for } \quad k=1,2, \ldots, n-1

$$

|

(provided by the Canadian Problems Committee).

Write $S_{k}$ as $\sum_{i=1}^{\binom{n}{k}} t_{i}$. Then

주

$$

S_{n-k}=\left(\prod_{m=1}^{n} a_{m}\right)\left(\sum_{i=1}^{\binom{n}{k}} \frac{1}{t_{i}}\right)

$$

$$

\text { so that } \left.\begin{array}{rl}

S_{k} S_{n-k} & =\left(\prod_{m=1}^{n} a_{m}\right) \cdot\left(\begin{array}{l}

\binom{n}{k} \\

i=1

\end{array} t_{i}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}

\binom{n}{k} \\

\sum_{j=1}^{2}

\end{array} \frac{1}{t_{j}}\right) \\

& =\left(\prod_{m=1}^{n} a_{m}\right)\left[\sum_{i=1}^{\binom{n}{k}} 1+\sum_{i=1}^{\binom{n}{k}} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \begin{array}{l}

n \\

k

\end{array}\right) \\

\frac{t_{i}}{} \\

t_{j}

\end{array}\right] .

$$

As there are

$$

\frac{\binom{n}{k}^{2}-\binom{n}{k}}{2}

$$

terms in the sum

$$

\begin{aligned}

S_{k} S_{n-k} & \geq\left(\prod_{m=1}^{n} a_{m}\right)\left[\binom{n}{k}+2 \cdot \frac{\binom{n}{k}^{2}-\binom{n}{k}}{2}\right] \\

& =\binom{n}{k}^{2}\left(\prod_{m=1}^{n} a_{m}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

since $\frac{t_{i}}{t_{j}}+\frac{t_{j}}{t_{i}} \geq 2$ for $t_{i}, t_{j}>0$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Question 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1990_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSECOND SOLUTION "

}

| 128

| 512

|

1990

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

A set of 1990 persons is divided into non-intersecting subsets in such a way that

(a) no one in a subset knows all the others in the subset;

(b) among any three persons in a subset, there are always at least two who do not know each other; and

(c) for any two persons in a subset who do not know each other, there is exactly one person in the same subset knowing both of them.

(i) Prove that within each subset, every person has the same number of acquaintances.

(ii) Determine the maximum possible number of subsets.

Note: it is understood that if a person $A$ knows person $B$, then person $B$ will know person $A$; an acquaintance is someone who is known. Every person is assumed to know one's self.

|

(i) Let $S$ be a subset of persons satisfying conditions (a), (b) and (c). Let $x \in S$ be one who knows the maximum number of persons in $S$.

Assume that $x$ knows $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$. By (b), $x_{i}$ and $x_{j}$ are strangers if $i \neq j$. For each $x_{i}$, let $N_{i}$ be the set of persons in $S$ who know $x_{i}$ but not $x$. Note that, for $i \neq j, N_{i}$ has no person in common with $N_{j}$, otherwise there would be more than one person knowing $x_{i}$ and $x_{j}$, contradicting (c).

By (a) we may assume that $N_{1}$ is not empty.) Let $y_{1} \in N_{1}$. By (c), for each $k>1$, there is exactly one person $y_{k}$ in $N_{k}$ who knows $y_{1}$. This means that $y_{1}$ knows $n$ persons, namely $x_{1}, y_{2}, \ldots, y_{n}$.

Because $n$ is the maximal number of persons in $S$ a person in $S$ can know, $y_{1}$ knows exactly $n$ persons in $S$. By precisely the same reasoning we find that each person in $N_{i}$, $i=1,2, \ldots, n$, knows exactly $n$ persons in $S$.

Letting $y_{1}$ take the role of $x$ in our argument, we see that also each $x_{i}$ knows exactly $n$ persons. Note that, by (c), every person in $S$ other than $x, x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}$, must be in some $N_{j}$. Therefore every person in $S$ knows exactly $n$ persons in $S$ and thus has the same number of acquaintances in $S$.

(ii) To maximize the number of subsets, we have to minimize the size of each group. The smallest possible subset is one in which every person knows exactly two persons, and hence there must be exactly five persons in the subset, forming a cycle where two persons stand side by side only if they know each other. Therefore the maximum possible number of subsets is 1990/5 $=398$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Question 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1990_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# SOLUTION:"

}

| 169

| 550

|

1991

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

During a break, $n$ children at school sit in a circle around their teacher to play a game. The teacher walks clockwise close to the children and hands out candies to some of them according to the following rule. He selects one child and gives him a candy, then he skips the next child and gives a candy to the next one, then he skips 2 and gives a candy to the next one, then he skips 3, and soon. Determine the values of $n$ for which eventually, perhaps after many rounds, all children will have at least one candy each.

Answer: All powers of 2 .

|

Number the children from 0 to $n-1$. Then the teacher hands candy to children in positions $f(x)=1+2+\cdots+x \bmod n=\frac{x(x+1)}{2} \bmod n$. Our task is to find the range of $f: \mathbb{Z}_{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{n}$, and to verify whether the range is $\mathbb{Z}_{n}$, that is, whether $f$ is a bijection.

If $n=2^{a} m, m>1$ odd, look at $f(x)$ modulo $m$. Since $m$ is odd, $m|f(x) \Longleftrightarrow m| x(x+1)$. Then, for instance, $f(x) \equiv 0(\bmod m)$ for $x=0$ and $x=m-1$. This means that $f(x)$ is not a bijection modulo $m$, and there exists $t$ such that $f(x) \not \equiv t(\bmod m)$ for all $x$. By the Chinese Remainder Theorem,

$$

f(x) \equiv t \quad(\bmod n) \Longleftrightarrow \begin{cases}f(x) \equiv t & \left(\bmod 2^{a}\right) \\ f(x) \equiv t & (\bmod m)\end{cases}

$$

Therefore, $f$ is not a bijection modulo $n$.

If $n=2^{a}$, then

$$

f(x)-f(y)=\frac{1}{2}(x(x+1)-y(y+1))=\frac{1}{2}\left(x^{2}-y^{2}+x-y\right)=\frac{(x-y)(x+y+1)}{2} .

$$

and

$$

f(x) \equiv f(y) \quad\left(\bmod 2^{a}\right) \Longleftrightarrow(x-y)(x+y+1) \equiv 0 \quad\left(\bmod 2^{a+1}\right)

$$

If $x$ and $y$ have the same parity, $x+y+1$ is odd and $(*)$ is equivalent to $x \equiv y\left(\bmod 2^{a+1}\right)$. If $x$ and $y$ have different parity,

$$

(*) \Longleftrightarrow x+y+1 \equiv 0 \quad\left(\bmod 2^{a+1}\right)

$$

However, $1 \leq x+y+1 \leq 2\left(2^{a}-1\right)+1=2^{a+1}-1$, so $x+y+1$ is not a multiple of $2^{a+1}$. Therefore $f$ is a bijection if $n$ is a power of 2 .

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1991_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1"

}

| 126

| 619

|

1991

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

During a break, $n$ children at school sit in a circle around their teacher to play a game. The teacher walks clockwise close to the children and hands out candies to some of them according to the following rule. He selects one child and gives him a candy, then he skips the next child and gives a candy to the next one, then he skips 2 and gives a candy to the next one, then he skips 3, and soon. Determine the values of $n$ for which eventually, perhaps after many rounds, all children will have at least one candy each.

Answer: All powers of 2 .

|

We give a full description of $a_{n}$, the size of the range of $f$.

Since congruences modulo $n$ are defined, via Chinese Remainder Theorem, by congruences modulo $p^{\alpha}$ for all prime divisors $p$ of $n$ and $\alpha$ being the number of factors $p$ in the factorization of $n, a_{n}=\prod_{p^{\alpha} \| n} a_{p^{\alpha}}$.

Refer to the first solution to check the case $p=2: a_{2^{\alpha}}=2^{\alpha}$.

For an odd prime $p$,

$$

f(x)=\frac{x(x+1)}{2}=\frac{(2 x+1)^{2}-1}{8}

$$

and since $p$ is odd, there is a bijection between the range of $f$ and the quadratic residues modulo $p^{\alpha}$, namely $t \mapsto 8 t+1$. So $a_{p^{\alpha}}$ is the number of quadratic residues modulo $p^{\alpha}$.

Let $g$ be a primitive root of $p^{\alpha}$. Then there are $\frac{1}{2} \phi\left(p^{\alpha}\right)=\frac{p-1}{2} \cdot p^{\alpha-1}$ quadratic residues that are coprime with $p: 1, g^{2}, g^{4}, \ldots, g^{\phi\left(p^{n}\right)-2}$. If $p$ divides a quadratic residue $k p$, that is, $x^{2} \equiv k p$ $\left(\bmod p^{\alpha}\right), \alpha \geq 2$, then $p$ divides $x$ and, therefore, also $k$. Hence $p^{2}$ divides this quadratic residue, and these quadratic residues are $p^{2}$ times each quadratic residue of $p^{\alpha-2}$. Thus

$$

a_{p^{\alpha}}=\frac{p-1}{2} \cdot p^{\alpha-1}+a_{p^{\alpha}-2} .

$$

Since $a_{p}=\frac{p-1}{2}+1$ and $a_{p^{2}}=\frac{p-1}{2} \cdot p+1$, telescoping yields

$$

a_{p^{2 t}}=\frac{p-1}{2}\left(p^{2 t-1}+p^{2 t-3}+\cdots+p\right)+1=\frac{p\left(p^{2 t}-1\right)}{2(p+1)}+1

$$

and

$$

a_{p^{2 t-1}}=\frac{p-1}{2}\left(p^{2 t-2}+p^{2 t-4}+\cdots+1\right)+1=\frac{p^{2 t}-1}{2(p+1)}+1

$$

Now the problem is immediate: if $n$ is divisible by an odd prime $p, a_{p^{\alpha}}<p^{\alpha}$ for all $\alpha$, and since $a_{t} \leq t$ for all $t, a_{n}<n$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1991_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2"

}

| 126

| 717

|

1992

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n$ be an integer such that $n>3$. Suppose that we choose three numbers from the set $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. Using each of these three numbers only once and using addition, multiplication, and parenthesis, let us form all possible combinations.

(a) Show that if we choose all three numbers greater than $n / 2$, then the values of these combinations are all distinct.

(b) Let $p$ be a prime number such that $p \leq \sqrt{n}$. Show that the number of ways of choosing three numbers so that the smallest one is $p$ and the values of the combinations are not all distinct is precisely the number of positive divisors of $p-1$.

|

In both items, the smallest chosen number is at least 2: in part (a), $n / 2>1$ and in part (b), $p$ is a prime. So let $1<x<y<z$ be the chosen numbers. Then all possible combinations are

$$

x+y+z, \quad x+y z, \quad x y+z, \quad y+z x, \quad(x+y) z, \quad(z+x) y, \quad(x+y) z, \quad x y z

$$

Since, for $1<m<n$ and $t>1,(m-1)(n-1) \geq 1 \cdot 2 \Longrightarrow m n>m+n, t n+m-(t m+n)=$ $(t-1)(n-m)>0 \Longrightarrow t n+m>t m+n$, and $(t+m) n-(t+n) m=t(n-m)>0$,

$$

x+y+z<z+x y<y+z x<x+y z

$$

and

$$

(y+z) x<(x+z) y<(x+y) z<x y z .

$$

Also, $(y+z) x-(y+z x)=(x-1) y>0 \Longrightarrow(y+z) x>y+z x$ and $(x+z) y-(x+y z)=$ $(y-1) x>0 \Longrightarrow(x+z) y>x+y z$. Therefore the only numbers that can be equal are $x+y z$ and $(y+z) x$. In this case,

$$

x+y z=(y+z) x \Longleftrightarrow(y-x)(z-x)=x(x-1)

$$

Now we can solve the items.

(a) if $n / 2<x<y<z$ then $z-x<n / 2$, and since $y-x<z-x, y-x<n / 2-1$; then

$$

(y-x)(z-x)<\frac{n}{2}\left(\frac{n}{2}-1\right)<x(x-1)

$$

and therefore $x+y z<(y+z) x$.

(b) if $x=p$, then $(y-p)(z-p)=p(p-1)$. Since $y-p<z-p,(y-p)^{2}<(y-p)(z-p)=$ $p(p-1) \Longrightarrow y-p<p$, that is, $p$ does not divide $y-p$. Then $y-p$ is a divisor $d$ of $p-1$ and $z-p=\frac{p(p-1)}{d}$. Therefore,

$$

x=p, \quad, y=p+d, \quad z=p+\frac{p(p-1)}{d}

$$

which is a solution for every divisor $d$ of $p-1$ because

$$

x=p<y=p+d<2 p \leq p+p \cdot \frac{p-1}{d}=z .

$$

Comment: If $x=1$ was allowed, then any choice $1, y, z$ would have repeated numbers in the combination, as $1 \cdot y+z=y+1 \cdot z$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1992_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 154

| 666

|

1992

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Determine all pairs $(h, s)$ of positive integers with the following property: If one draws $h$ horizontal lines and another $s$ lines which satisfy

(i) they are not horizontal,

(ii) no two of them are parallel,

(iii) no three of the $h+s$ lines are concurrent,

then the number of regions formed by these $h+s$ lines is 1992 .

Answer: $(995,1),(176,10)$, and $(80,21)$.

|

Let $a_{h, s}$ the number of regions formed by $h$ horizontal lines and $s$ another lines as described in the problem. Let $\mathcal{F}_{h, s}$ be the union of the $h+s$ lines and pick any line $\ell$. If it intersects the other lines in $n$ (distinct!) points then $\ell$ is partitioned into $n-1$ line segments and 2 rays, which delimit regions. Therefore if we remove $\ell$ the number of regions decreases by exactly $n-1+2=n+1$.

Then $a_{0,0}=1$ (no lines means there is only one region), and since every one of $s$ lines intersects the other $s-1$ lines, $a_{0, s}=a_{0, s-1}+s$ for $s \geq 0$. Summing yields

$$

a_{0, s}=s+(s-1)+\cdots+1+a_{0,0}=\frac{s^{2}+s+2}{2} .

$$

Each horizontal line only intersects the $s$ non-horizontal lines, so $a_{h, s}=a_{h-1, s}+s+1$, which implies

$$

a_{h, s}=a_{0, s}+h(s+1)=\frac{s^{2}+s+2}{2}+h(s+1) .

$$

Our final task is solving

$$

a_{h, s}=1992 \Longleftrightarrow \frac{s^{2}+s+2}{2}+h(s+1)=1992 \Longleftrightarrow(s+1)(s+2 h)=2 \cdot 1991=2 \cdot 11 \cdot 181

$$

The divisors of $2 \cdot 1991$ are $1,2,11,22,181,362,1991,3982$. Since $s, h>0,2 \leq s+1<s+2 h$, so the possibilities for $s+1$ can only be 2,11 and 22 , yielding the following possibilities for $(h, s)$ :

$$

(995,1), \quad(176,10), \quad \text { and }(80,21) .

$$

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1992_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 111

| 524

|

1992

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Find a sequence of maximal length consisting of non-zero integers in which the sum of any seven consecutive terms is positive and that of any eleven consecutive terms is negative.

Answer: The maximum length is 16 . There are several possible sequences with this length; one such sequence is $(-7,-7,18,-7,-7,-7,18,-7,-7,18,-7,-7,-7,18,-7,-7)$.

|

Suppose it is possible to have more than 16 terms in the sequence. Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{17}$ be the first 17 terms of the sequence. Consider the following array of terms in the sequence:

| $a_{1}$ | $a_{2}$ | $a_{3}$ | $a_{4}$ | $a_{5}$ | $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| $a_{2}$ | $a_{3}$ | $a_{4}$ | $a_{5}$ | $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ |

| $a_{3}$ | $a_{4}$ | $a_{5}$ | $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ | $a_{13}$ |

| $a_{4}$ | $a_{5}$ | $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ | $a_{13}$ | $a_{14}$ |

| $a_{5}$ | $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ | $a_{13}$ | $a_{14}$ | $a_{15}$ |

| $a_{6}$ | $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ | $a_{13}$ | $a_{14}$ | $a_{15}$ | $a_{16}$ |

| $a_{7}$ | $a_{8}$ | $a_{9}$ | $a_{10}$ | $a_{11}$ | $a_{12}$ | $a_{13}$ | $a_{14}$ | $a_{15}$ | $a_{16}$ | $a_{17}$ |

Let $S$ the sum of the numbers in the array. If we sum by rows we obtain negative sums in each row, so $S<0$; however, it we sum by columns we obtain positive sums in each column, so $S>0$, a contradiction. This implies that the sequence cannot have more than 16 terms. One idea to find a suitable sequence with 16 terms is considering cycles of 7 numbers. For instance, one can try

$$

-a,-a, b,-a,-a,-a, b,-a,-a, b,-a,-a,-a, b,-a,-a .

$$

The sum of every seven consecutive numbers is $-5 a+2 b$ and the sum of every eleven consecutive numbers is $-8 a+3 b$, so $-5 a+2 b>0$ and $-8 a+3 b<0$, that is,

$$

\frac{5 a}{2}<b<\frac{8 a}{3} \Longleftrightarrow 15 a<6 b<16 a

$$

Then we can choose, say, $a=7$ and $105<6 b<112 \Longleftrightarrow b=18$. A valid sequence is then

$$

-7,-7,18,-7,-7,-7,18,-7,-7,18,-7,-7,-7,18,-7,-7

$$

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1992_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 94

| 913

|

1993

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Find the total number of different integer values the function

$$

f(x)=[x]+[2 x]+\left[\frac{5 x}{3}\right]+[3 x]+[4 x]

$$

takes for real numbers $x$ with $0 \leq x \leq 100$.

Note: $[t]$ is the largest integer that does not exceed $t$.

Answer: 734.

|

Note that, since $[x+n]=[x]+n$ for any integer $n$,

$$

f(x+3)=[x+3]+[2(x+3)]+\left[\frac{5(x+3)}{3}\right]+[3(x+3)]+[4(x+3)]=f(x)+35,

$$

one only needs to investigate the interval $[0,3)$.

The numbers in this interval at which at least one of the real numbers $x, 2 x, \frac{5 x}{3}, 3 x, 4 x$ is an integer are

- $0,1,2$ for $x$;

- $\frac{n}{2}, 0 \leq n \leq 5$ for $2 x$;

- $\frac{3 n}{5}, 0 \leq n \leq 4$ for $\frac{5 x}{3}$;

- $\frac{n}{3}, 0 \leq n \leq 8$ for $3 x$;

- $\frac{n}{4}, 0 \leq n \leq 11$ for $4 x$.

Of these numbers there are

- 3 integers $(0,1,2)$;

- 3 irreducible fractions with 2 as denominator (the numerators are $1,3,5$ );

- 6 irreducible fractions with 3 as denominator (the numerators are $1,2,4,5,7,8$ );

- 6 irreducible fractions with 4 as denominator (the numerators are $1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15$ );

- 4 irreducible fractions with 5 as denominator (the numerators are 3,6,9,12).

Therefore $f(x)$ increases 22 times per interval. Since $100=33 \cdot 3+1$, there are $33 \cdot 22$ changes of value in $[0,99)$. Finally, there are 8 more changes in [99,100]: 99, 100, $99 \frac{1}{2}, 99 \frac{1}{3}, 99 \frac{2}{3}, 99 \frac{1}{4}$, $99 \frac{3}{4}, 99 \frac{3}{5}$.

The total is then $33 \cdot 22+8=734$.

Comment: A more careful inspection shows that the range of $f$ are the numbers congruent modulo 35 to one of

$$

0,1,2,4,5,6,7,11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,23,24,25,26,28,29,30

$$

in the interval $[0, f(100)]=[0,1166]$. Since $1166 \equiv 11(\bmod 35)$, this comprises 33 cycles plus the 8 numbers in the previous list.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1993_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 92

| 691

|

1993

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let

$$

f(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+\cdots+a_{0} \quad \text { and } \quad g(x)=c_{n+1} x^{n+1}+c_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+c_{0}

$$

be non-zero polynomials with real coefficients such that $g(x)=(x+r) f(x)$ for some real number $r$. If $a=\max \left(\left|a_{n}\right|, \ldots,\left|a_{0}\right|\right)$ and $c=\max \left(\left|c_{n+1}\right|, \ldots,\left|c_{0}\right|\right)$, prove that $\frac{a}{c} \leq n+1$.

|

Expanding $(x+r) f(x)$, we find that $c_{n+1}=a_{n}, c_{k}=a_{k-1}+r a_{k}$ for $k=1,2, \ldots, n$, and $c_{0}=r a_{0}$. Consider three cases:

- $r=0$. Then $c_{0}=0$ and $c_{k}=a_{k-1}$ for $k=1,2, \ldots, n$, and $a=c \Longrightarrow \frac{a}{c}=1 \leq n+1$.

- $|r| \geq 1$. Then

$$

\begin{gathered}

\left|a_{0}\right|=\left|\frac{c_{0}}{r}\right| \leq c \\

\left|a_{1}\right|=\left|\frac{c_{1}-a_{0}}{r}\right| \leq\left|c_{1}\right|+\left|a_{0}\right| \leq 2 c

\end{gathered}

$$

and inductively if $\left|a_{k}\right| \leq(k+1) c$

$$

\left|a_{k+1}\right|=\left|\frac{c_{k+1}-a_{k}}{r}\right| \leq\left|c_{k+1}\right|+\left|a_{k}\right| \leq c+(k+1) c=(k+2) c

$$

Therefore, $\left|a_{k}\right| \leq(k+1) c \leq(n+1) c$ for all $k$, and $a \leq(n+1) c \Longleftrightarrow \frac{a}{c} \leq n+1$.

- $0<|r|<1$. Now work backwards: $\left|a_{n}\right|=\left|c_{n+1}\right| \leq c$,

$$

\left|a_{n-1}\right|=\left|c_{n}-r a_{n}\right| \leq\left|c_{n}\right|+\left|r a_{n}\right|<c+c=2 c,

$$

and inductively if $\left|a_{n-k}\right| \leq(k+1) c$

$$

\left|a_{n-k-1}\right|=\left|c_{n-k}-r a_{n-k}\right| \leq\left|c_{n-k}\right|+\left|r a_{n-k}\right|<c+(k+1) c=(k+2) c .

$$

Therefore, $\left|a_{n-k}\right| \leq(k+1) c \leq(n+1) c$ for all $k$, and $a \leq(n+1) c$ again.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1993_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 185

| 643

|

1994

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

Let $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be a function such that

(i) For all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$,

$$

f(x)+f(y)+1 \geq f(x+y) \geq f(x)+f(y)

$$

(ii) For all $x \in[0,1), f(0) \geq f(x)$,

(iii) $-f(-1)=f(1)=1$.

Find all such functions $f$.

Answer: $f(x)=\lfloor x\rfloor$, the largest integer that does not exceed $x$, is the only function.

|

Plug $y \rightarrow 1$ in (i):

$$

f(x)+f(1)+1 \geq f(x+1) \geq f(x)+f(1) \Longleftrightarrow f(x)+1 \leq f(x+1) \leq f(x)+2

$$

Now plug $y \rightarrow-1$ and $x \rightarrow x+1$ in (i):

$$

f(x+1)+f(-1)+1 \geq f(x) \geq f(x+1)+f(-1) \Longleftrightarrow f(x) \leq f(x+1) \leq f(x)+1

$$

Hence $f(x+1)=f(x)+1$ and we only need to define $f(x)$ on $[0,1)$. Note that $f(1)=$ $f(0)+1 \Longrightarrow f(0)=0$.

Condition (ii) states that $f(x) \leq 0$ in $[0,1)$.

Now plug $y \rightarrow 1-x$ in (i):

$$

f(x)+f(1-x)+1 \leq f(x+(1-x)) \leq f(x)+f(1-x) \Longrightarrow f(x)+f(1-x) \geq 0

$$

If $x \in(0,1)$ then $1-x \in(0,1)$ as well, so $f(x) \leq 0$ and $f(1-x) \leq 0$, which implies $f(x)+f(1-x) \leq 0$. Thus, $f(x)=f(1-x)=0$ for $x \in(0,1)$. This combined with $f(0)=0$ and $f(x+1)=f(x)+1$ proves that $f(x)=\lfloor x\rfloor$, which satisfies the problem conditions, as since

$x+y=\lfloor x\rfloor+\lfloor y\rfloor+\{x\}+\{y\}$ and $0 \leq\{x\}+\{y\}<2 \Longrightarrow\lfloor x\rfloor+\lfloor y\rfloor \leq x+y<\lfloor x\rfloor+\lfloor y\rfloor+2$ implies

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor+\lfloor y\rfloor+1 \geq\lfloor x+y\rfloor \geq\lfloor x\rfloor+\lfloor y\rfloor .

$$

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1994_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 145

| 548

|

1994

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n$ be an integer of the form $a^{2}+b^{2}$, where $a$ and $b$ are relatively prime integers and such that if $p$ is a prime, $p \leq \sqrt{n}$, then $p$ divides $a b$. Determine all such $n$.

Answer: $n=2,5,13$.

|

A prime $p$ divides $a b$ if and only if divides either $a$ or $b$. If $n=a^{2}+b^{2}$ is a composite then it has a prime divisor $p \leq \sqrt{n}$, and if $p$ divides $a$ it divides $b$ and vice-versa, which is not possible because $a$ and $b$ are coprime. Therefore $n$ is a prime.

Suppose without loss of generality that $a \geq b$ and consider $a-b$. Note that $a^{2}+b^{2}=(a-b)^{2}+2 a b$.

- If $a=b$ then $a=b=1$ because $a$ and $b$ are coprime. $n=2$ is a solution.

- If $a-b=1$ then $a$ and $b$ are coprime and $a^{2}+b^{2}=(a-b)^{2}+2 a b=2 a b+1=2 b(b+1)+1=$ $2 b^{2}+2 b+1$. So any prime factor of any number smaller than $\sqrt{2 b^{2}+2 b+1}$ is a divisor of $a b=b(b+1)$.

One can check that $b=1$ and $b=2$ yields the solutions $n=1^{2}+2^{2}=5$ (the only prime $p$ is 2 ) and $n=2^{2}+3^{2}=13$ (the only primes $p$ are 2 and 3 ). Suppose that $b>2$.

Consider, for instance, the prime factors of $b-1 \leq \sqrt{2 b^{2}+2 b+1}$, which is coprime with $b$. Any prime must then divide $a=b+1$. Then it divides $(b+1)-(b-1)=2$, that is, $b-1$ can only have 2 as a prime factor, that is, $b-1$ is a power of 2 , and since $b-1 \geq 2$, $b$ is odd.

Since $2 b^{2}+2 b+1-(b+2)^{2}=b^{2}-2 b-3=(b-3)(b+1) \geq 0$, we can also consider any prime divisor of $b+2$. Since $b$ is odd, $b$ and $b+2$ are also coprime, so any prime divisor of $b+2$ must divide $a=b+1$. But $b+1$ and $b+2$ are also coprime, so there can be no such primes. This is a contradiction, and $b \geq 3$ does not yield any solutions.

- If $a-b>1$, consider a prime divisor $p$ of $a-b=\sqrt{a^{2}-2 a b+b^{2}}<\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}}$. Since $p$ divides one of $a$ and $b, p$ divides both numbers (just add or subtract $a-b$ accordingly.) This is a contradiction.

Hence the only solutions are $n=2,5,13$.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1994_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 82

| 721

|

1994

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

You are given three lists $A, B$, and $C$. List $A$ contains the numbers of the form $10^{k}$ in base 10, with $k$ any integer greater than or equal to 1 . Lists $B$ and $C$ contain the same numbers translated into base 2 and 5 respectively:

| $A$ | $B$ | $C$ |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 10 | 1010 | 20 |

| 100 | 1100100 | 400 |

| 1000 | 1111101000 | 13000 |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

Prove that for every integer $n>1$, there is exactly one number in exactly one of the lists $B$ or $C$ that has exactly $n$ digits.

|

Let $b_{k}$ and $c_{k}$ be the number of digits in the $k$ th term in lists $B$ and $C$, respectively. Then

$$

2^{b_{k}-1} \leq 10^{k}<2^{b_{k}} \Longleftrightarrow \log _{2} 10^{k}<b_{k} \leq \log _{2} 10^{k}+1 \Longleftrightarrow b_{k}=\left\lfloor k \cdot \log _{2} 10\right\rfloor+1

$$

and, similarly

$$

c_{k}=\left\lfloor k \cdot \log _{5} 10\right\rfloor+1

$$

Beatty's theorem states that if $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are irrational positive numbers such that

$$

\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}=1

$$

then the sequences $\lfloor k \alpha\rfloor$ and $\lfloor k \beta\rfloor, k=1,2, \ldots$, partition the positive integers.

Then, since

$$

\frac{1}{\log _{2} 10}+\frac{1}{\log _{5} 10}=\log _{10} 2+\log _{10} 5=\log _{10}(2 \cdot 5)=1

$$

the sequences $b_{k}-1$ and $c_{k}-1$ partition the positive integers, and therefore each integer greater than 1 appears in $b_{k}$ or $c_{k}$ exactly once. We are done.

Comment: For the sake of completeness, a proof of Beatty's theorem follows.

Let $x_{n}=\alpha n$ and $y_{n}=\beta n, n \geq 1$ integer. Note that, since $\alpha m=\beta n$ implies that $\frac{\alpha}{\beta}$ is rational but

$$

\frac{\alpha}{\beta}=\alpha \cdot \frac{1}{\beta}=\alpha\left(1-\frac{1}{\alpha}\right)=\alpha-1

$$

is irrational, the sequences have no common terms, and all terms in both sequences are irrational.

The theorem is equivalent to proving that exactly one term of either $x_{n}$ of $y_{n}$ lies in the interval $(N, N+1)$ for each $N$ positive integer. For that purpose we count the number of terms of the union of the two sequences in the interval $(0, N)$ : since $n \alpha<N \Longleftrightarrow n<\frac{N}{\alpha}$, there are $\left\lfloor\frac{N}{\alpha}\right\rfloor$ terms of $x_{n}$ in the interval and, similarly, $\left\lfloor\frac{N}{\beta}\right\rfloor$ terms of $y_{n}$ in the same interval. Since the sequences are disjoint, the total of numbers is

$$

T(N)=\left\lfloor\frac{N}{\alpha}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{N}{\beta}\right\rfloor

$$

However, $x-1<\lfloor x\rfloor<x$ for nonintegers $x$, so

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{N}{\alpha}-1+\frac{N}{\beta}-1<T(N)<\frac{N}{\alpha}+\frac{N}{\beta} & \Longleftrightarrow N\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}\right)-2<T(N)<N\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}\right) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow N-2<T(N)<N,

\end{aligned}

$$

that is, $T(N)=N-1$.

Therefore the number of terms in $(N, N+1)$ is $T(N+1)-T(N)=N-(N-1)=1$, and the result follows.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1994_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 209

| 899

|

1999

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Let $S$ be a set of $2 n+1$ points in the plane such that no three are collinear and no four concyclic. A circle will be called good if it has 3 points of $S$ on its circumference, $n-1$ points in its interior and $n-1$ in its exterior. Prove that the number of good circles has the same parity as $n$.

|

and Marking Scheme:

Lemma 1. Let $P$ and $Q$ be two points of $S$. The number of good circles that contain $P$ and $Q$ on their circumference is odd.

## Proof of Lemma 1.

Let $N$ be the number of good circles that pass through $P$ and $Q$. Number the points on one side of the line $P Q$ by $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{k}$ and those on the other side by $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{m}$ in such a way that if $\angle P A_{i} Q=\alpha_{i}, \angle P B_{j} Q=180-\beta_{j}$ then $\alpha_{1}>\alpha_{2}>\ldots>\alpha_{k}$ and $\beta_{1}>\beta_{2}>\ldots>\beta_{m}$.

Note that the angles $\alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}, \ldots, \alpha_{k}, \beta_{1}, \beta_{2}, \ldots, \beta_{m}$ are all distinct since there are no four points in $S$ that are concyclic.

Observe that the circle that passes through $P, Q$ and $A_{i}$ has $A_{j}$ in its interior when $\alpha_{j}>\alpha_{i}$ that is, when $i>j$; and it contains $B_{j}$ in its interior when $\alpha_{i}+180-\beta_{j}>180$, that is, when $\alpha_{i}>\beta_{j}$. Similar conditions apply to the circle that contains $P, Q$ and $B_{j}$.

1 POINT for characterizing the points that lie inside a given circle ins terms of these angles, or for similar considerations.

Order the angles $\alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}, \ldots, \alpha_{k}, \beta_{1}, \beta_{2}, \ldots, \beta_{m}$ from the greatest to least. Now transform $S$ as follows. Consider a $\beta_{j}$ that bas an $\alpha_{i}$ immediately to its left in such an ordering ( $\ldots>\alpha_{i}>\beta_{j} \ldots$ ). Consider a new set $S^{\prime}$ that contains the same points as $S$ except for $A_{i}$ and $B_{j}$. These two points will be replaced by $A_{i}^{\prime}$ and $B_{j}^{\prime}$ that satisfy $\angle P A_{i}^{\prime} Q=\beta_{j}=\alpha_{i}^{\prime}$ and $\angle P B_{j}^{\prime} Q=180-\alpha_{i}^{\prime \prime}=180-\beta_{j}^{\prime}$. Thus $\beta_{j}$ and $\alpha_{i}$ have been interchanged and the ordering of the $\alpha$ 's and $\beta$ 's has only changed with respect to the relative order of $\alpha_{i}$ and $\beta_{j}$; we continue to have

$$

\alpha_{1}>\alpha_{2}>\ldots>\alpha_{i-1}>\alpha_{i}^{\prime}>\alpha_{i+1}>\ldots>\alpha_{k}

$$

and

$$

\beta_{1}>\beta_{2}>\ldots>\beta_{j-1}>\beta_{j}^{\prime}>\beta_{j+1}>\ldots>\beta_{m}

$$

1 POINT for this or another useful transformation of the set $S$.

Analyze the good circles in this new set $S^{\prime}$. Clearly, a circle through $P, Q, A_{r}(r \neq i)$ or through $P, Q, B_{s}(s \neq j)$ that was good in $S$ will also be good in $S^{\prime}$, because the order of $A_{r}$ (or $B_{s}$ ) relative to the rest of the points has not changed, and therefore the number of points in the interior or exterior of this circle has not changed. The only changes that could have taken place are:

a) If the circle $P, Q, A_{i}$ was good in $S$, the circle $P, Q, A_{i}^{\prime}$ may not be good in $S^{\prime}$.

b) If the circle $P, Q, B_{j}$ was good in $S$, the circle $P, Q, B_{j}^{\prime}$ may not be good in $S^{\prime}$.

c) If the circle $P, Q, A_{i}$ was not good in $S$, the circle $P, Q, A_{i}^{\prime}$ may be good in $S^{\prime}$.

d) If the circle $P, Q, B_{j}$ was not good in $S$, the circle $P, Q, B_{j}^{\prime}$ may be good in $S^{\prime}$.

1 POINT for realizing that the transformation can only change the "goodness" of these circles. But observe that the circle $P, Q, A_{i}$ contains the points $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{i-1}, B_{j}, B_{j+1}, \ldots, B_{m}$ and does not contain the points $A_{i+1}, A_{i+2}, \ldots, A_{k}, B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{j-1}$ in its interior. Then this circle is good if and only if $i+m-j=k-i+j-1$, which we rewrite as $j-i=\frac{1}{2}(m-k+1)$. On the other hand, the circle $P, Q, B_{j}$ contains the points $B_{j+1}, B_{j+2}, \ldots, B_{m}, A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{i}$ and does not contain the points $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{j-1}, A_{i+1}, A_{i+2}, \ldots, A_{k}$ in its interior. Hence this circle is good if and only if $m-j+i=j-1+k-i$, which we rewrite as $j-i=\frac{1}{2}(m-k+1)$.

Therefore, the circle $P, Q, A_{i}$ is good if and only if the circle $P, Q, B_{j}$ is good. Similarly, the circle $P, Q, A_{i}^{\prime}$ is good if and only if the circle $P, Q, B_{j}^{\prime}$ is good. That is to say, transforming $S$ into $S^{\prime}$ we lose either 0 or 2 good circles of $S$ and we gain either 0 or 2 good circles in $S^{\prime}$.

1 POINT for realizing that the "goodness" of these circles is changed in pairs.

Continuing in this way, we may continue to transform $S$ until we obtain a new set $S_{0}$ such that the angles $\alpha_{1}^{\prime}, \alpha_{2}^{\prime}, \ldots, \alpha_{k}^{\prime}, \beta_{1}^{\prime}, \beta_{2}^{\prime}, \ldots, \beta_{m}^{\prime}$ satisfy

$$

\beta_{1}^{\prime}>\beta_{2}^{\prime}>\ldots>\beta_{n}^{\prime}>\alpha_{1}^{\prime}>\alpha_{2}^{\prime}>\ldots>\alpha_{k}^{\prime}

$$

and such that the number of good circles in $S_{0}$ has the same parity as $N$. We claim that $S_{0}$ has exactly one good circle. In this configuration, the circle $P, Q, A_{i}$ does not contain any $B_{j}$ and the circle $P, Q, B_{r}$ does not contain any $A_{s}$ (for all $\left.i, j\right)$, because $\alpha_{a}+\left(180-\beta_{b}\right)<180$ for all $a, b$. Hence, the only possible good circles are $P, Q, B_{m-n+1}$ (which contains the $n-1$ points $B_{m-n+2}, B_{m-n+3}, \ldots, B_{m}$ ), if $m-n+1>0$, and the circle $P, Q, A_{n}$ (which contains the $n-1$ points $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{n}$ ), if $n \leq k$. But, since $m+k=2 n-1$, which we rewrite as $m-n+1=n-k$, exactly one of the inequalitites $m-n+1>0$ and $n \leq k$ is satisfied. It follows that one of the points $B_{m-n+1}$ and $A_{n}$ corresponds to a good circle and the other does not. Hence, $S_{0}$ has exactly one good circle, and $N$ is odd.

1 POINT for showing that this configuration has exactly one good circle.

Now consider the $\binom{2 n+1}{2}$ pairs of points in $S$. Let $a_{2 k+1}$ be the number of pairs of points through which exactly $2 k+1$ good circles pass. Then

$$

a_{1}+a_{3}+a_{5}+\ldots=\binom{2 n+1}{2}

$$

But then the number of good circles in $S$ is

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{3}\left(a_{1}+3 a_{3}+5 a_{5}+7 a_{7}+\ldots\right) & \equiv a_{1}+3 a_{3}+5 a_{5}+7 a_{7}+\ldots \\

& \equiv a_{1}+a_{3}+a_{5}+a_{7}+\ldots \\

& \equiv\binom{2 n+1}{2} \\

& \equiv n(2 n+1) \\

& \equiv n(\bmod 2) .

\end{aligned}

$$

Here we have taken into account that each good circle is counted 3 times in the expression $a_{1}+3 a_{3}+$ $5 a_{5}+7 a_{7}+\ldots$ The desired result follows.

2 POINTS for this computation.

## Alteraative Proof of Lemma 1.

Let, $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{2 n-1}$ be the $2 n-1$ given points other than $P$ and $Q$.

Invert the plane with respect to point $P$. Let $O, B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{2 n-1}$ be the images of points $Q, A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{2 n-1}$, respectively, under this inversion. Call point $B_{i}$ "good" if the line $O B_{i}$ splits the points $B_{1}, B_{2} \ldots, B_{i-1}, B_{i+1}, \ldots, B_{2 n-1}$ evenly, leaving $n-1$ of them to each side of it. (Notice that no other $B_{j}$ can lie on the line $O B_{i}$, or else the points $P, Q, A_{i}$ and $A_{j}$ would be concyclic.) Then it is clear that the circle through $P, Q$ and $A_{i}$ is good if and only if point $B_{i}$ is good. Therefore, it suffices to prove that the number of good points is odd.

1 POINT for inverting and realizing the equivalence between good circles and good points. Notice that the good points depend only on the relative positions of rays $O B_{1}, O B_{2}, \ldots, O B_{2 n-1}$, and not on the exact positions of points $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{2 n-1}$. Therefore we may assume, for simplicity, that $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{2 n-1}$ lie on the unit circle $\Gamma$ with center $O$.

1 POINT for this or a similar simplification.

Let $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{2 n-1}$ be the points diametrically opposite to $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{2 n-1}$ in $\Gamma$. As remarked earlier, no $C_{i}$ can coincide with one of the $B_{j}$ 's. We will call the $B_{i}$ 's "white points", and the $C_{i}$ 's "black points". We will refer to these $4 n-2$ points as the "colored points".

Now we prove that the number of good points is odd, which will complete the proof of the lemma. We proceed by induction on $n$. If $n=1$, the result is trivial. Now assume that the result is true for $n=k$, and consider $2 k+1$ white points $B_{1}, B_{2}, \ldots, B_{2 k+1}$ on the circle $\Gamma$ (no two of which are diametrically opposite), and their diametrically opposite black points $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{2 k+1}$. Call this configuration of points "configuration 1 ". It is clear that we must have two consecutive colored points on $\Gamma$ which have different colors, say $B_{i}$ and $C_{j}$. Now remove points $B_{i}, B_{j}, C_{i}$ and $C_{j}$ from $\Gamma$, to obtain "configuration 2 ", a configuration with $2 k-1$ points of each color.

1 POINT for this or a similar transformation of the set.

It is easy to verify the following two claims:

1. Point $B_{i}$ is good in configuration 1 if and only if point $B_{j}$ is good in configuration 1.

2. Let $k \neq i, j$. Then point $B_{k}$ is good in configuration 1 if and only if it is good in configuration 2.

It follows that, by removing points $B_{i}, B_{j}, C_{i}$ and $C_{j}$, the number of good points can either stay the same, or decreases by two. In any case, its parity remains unchanged. Since we know, by the induction hypothesis, that the number of good points in configuration 2 is odd, it follows that the number of good points in configuration 1 is also odd. This completes the proof.

## Another Approach to Lemma 1.

One can give another inductive proof of lemma. 1, which combines the ideas of the two proofs that we have given. The idea is to start as in the first proof, with the characterization of the points inside a given circle.

1 POINT

Then we transform the set $S$ by removing the points $A_{i}$ and $B_{j}$ instead of replacing then by $A_{i}^{p}$ and $B_{j}^{\prime}$.

1 POINT

It can be shown that every one of the romaining circles going through $P$ and $Q$, contained exactly one of $A_{i}$ and $B_{j}$. Therefore, the only good circles we could have gained or lost are $P, Q, A_{i}$ and $P, Q, B_{j}$.

2 POINTS

Finally, we show that either both or none of these circles were good, so the parity of the number of good circles isn't changed by this transformation.

1 POINT

Remark: 2 POINTS can be given if the result has been fully proved for a particular case with $n>1$. (If more than one particular case has been analyzed completly, only 2 POINTS.) These points are awarded only if no progress has been made in the general solution of the problem.

|

{

"problem_match": "\nProblem 5.",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo1999_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution "

}

| 86

| 3,594

|

2000

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

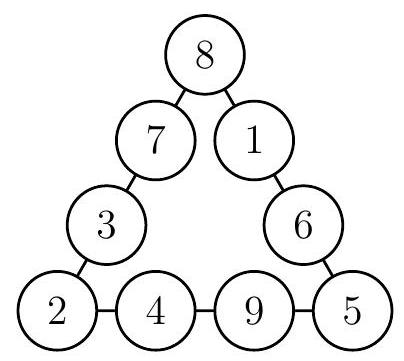

Given the following arrangement of circles:

Each of the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 9$ is to be written into one of these circles, so that each circle contains exactly one of these numbers and

(i) the sums of the four numbers on each side of the triangle are equal;

(ii) the sums of squares of the four numbers on each side of the triangle are equal.

Find all ways in which this can be done.

Answer: The only solutions are

and the ones generated by permuting the vertices, adjusting sides and exchanging the two middle numbers on each side.

|

Let $a, b$, and $c$ be the numbers in the vertices of the triangular arrangement. Let $s$ be the sum of the numbers on each side and $t$ be the sum of the squares of the numbers on each side. Summing the numbers (or their squares) on the three sides repeats each once the numbers on the vertices (or their squares):

$$

\begin{gathered}

3 s=a+b+c+(1+2+\cdots+9)=a+b+c+45 \\

3 t=a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+\left(1^{2}+2^{2}+\cdots+9^{2}\right)=a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+285

\end{gathered}

$$

At any rate, $a+b+c$ and $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}$ are both multiples of 3 . Since $x^{2} \equiv 0,1(\bmod 3)$, either $a, b, c$ are all multiples of 3 or none is a multiple of 3 . If two of them are $1,2 \bmod 3$ then $a+b+c \equiv 0(\bmod 3)$ implies that the other should be a multiple of 3 , which is not possible. Thus $a, b, c$ are all congruent modulo 3 , that is,

$$

\{a, b, c\}=\{3,6,9\}, \quad\{1,4,7\}, \quad \text { or } \quad\{2,5,8\}

$$

Case 1: $\{a, b, c\}=\{3,6,9\}$. Then $3 t=3^{2}+6^{2}+9^{2}+285 \Longleftrightarrow t=137$.

In this case $x^{2}+y^{2}+3^{2}+9^{2}=137 \Longleftrightarrow x^{2}+y^{2}=47$. However, 47 cannot be written as the sum of two squares. One can check manually, or realize that $47 \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, and since $x^{2}, y^{2} \equiv 0,1(\bmod 4), x^{2}+y^{2} \equiv 0,1,2(\bmod 4)$ cannot be 47.

Hence there are no solutions in this case.

Case 2: $\{a, b, c\}=\{1,4,7\}$. Then $3 t=1^{2}+4^{2}+7^{2}+285 \Longleftrightarrow t=117$.

In this case $x^{2}+y^{2}+1^{2}+7^{2}=117 \Longleftrightarrow x^{2}+y^{2}=67 \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, and as in the previous case there are no solutions.

Case 3: $\{a, b, c\}=\{2,5,8\}$. Then $3 t=2^{2}+5^{2}+8^{2}+285 \Longleftrightarrow t=126$.

Then

$$

\left\{\begin{array} { c }

{ x ^ { 2 } + y ^ { 2 } + 2 ^ { 2 } + 8 ^ { 2 } = 1 2 6 } \\

{ t ^ { 2 } + u ^ { 2 } + 2 ^ { 2 } + 5 ^ { 2 } = 1 2 6 } \\

{ m ^ { 2 } + n ^ { 2 } + 5 ^ { 2 } + 8 ^ { 2 } = 1 2 6 }

\end{array} \Longleftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{c}

x^{2}+y^{2}=58 \\

t^{2}+u^{2}=97 \\

m^{2}+n^{2}=37

\end{array}\right.\right.

$$

The only solutions to $t^{2}+u^{2}=97$ and $m^{2}+n^{2}=37$ are $\{t, u\}=\{4,9\}$ and $\{m, n\}=\{1,6\}$, respectively (again, one can check manually.) Then $\{x, y\}=\{3,7\}$, and the solutions are

and the ones generated by permuting the vertices, adjusting sides and exchanging the two middle numbers on each side. There are $3!\cdot 2^{3}=48$ such solutions.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2000_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 264

| 1,062

|

2000

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle. Let $M$ and $N$ be the points in which the median and angle bisector, respectively, at $A$ meet the side $B C$. Let $Q$ and $P$ be the points in which the perpendicular at $N$ to $N A$ meets $M A$ and $B A$, respectively, and $O$ be the point in which the perpendicular at $P$ to $B A$ meets $A N$ produced. Prove that $Q O$ is perpendicular to $B C$.

|

Consider a cartesian plane with $A=(0,0)$ as the origin and the bisector $A N$ as $x$-axis. Thus $A B$ has equation $y=m x$ and $A C$ has equation $y=-m x$. Let $B=(b, m b)$ and $C=(c,-m c)$. By symmetry, the problem is immediate if $A B=A C$, that is, if $b=c$. Suppose that $b \neq c$ from now on. Line $B C$ has slope $\frac{m b-(-m c)}{b-c}=\frac{m(b+c)}{b-c}$. Let $N=(n, 0)$.

Point $M$ is the midpoint $\left(\frac{b+c}{2}, \frac{m b-m c}{2}\right)$ of $B C$, so $A M$ has slope $\frac{m(b-c)}{b+c}$.

The line through $N$ that is perpendicular to the $x$-axis $A N$ is $x=n$. Therefore

$$

P=(n, m n) \quad \text { and } \quad Q=\left(n, \frac{m(b-c) n}{b+c}\right) .

$$

In the right triangle $A P O$, with altitude $A N, A N \cdot A O=A P^{2}$. Thus

$$

n \cdot A O=(0-n)^{2}+(0-m n)^{2} \Longleftrightarrow A O=n\left(m^{2}+1\right) \Longrightarrow O=\left(n\left(m^{2}+1\right), 0\right)

$$

Finally, the slope of $O Q$ is

$$

\frac{\frac{m(b-c) n}{b+c}-0}{n-n\left(m^{2}+1\right)}=-\frac{b-c}{(b+c) m}

$$

Since the product of the slopes of $O Q$ and $B C$ is

$$

-\frac{b-c}{(b+c) m} \cdot \frac{m(b+c)}{b-c}=-1

$$

$O Q$ and $B C$ are perpendicular, and we are done.

Comment: The second solution shows that $N$ can be any point in the bisector of $\angle A$. In fact, if we move $N$ in the bisector and construct $O, P$ and $Q$ accordingly, then all lines $O Q$ obtained are parallel: just consider a homothety with center $A$ and variable ratios.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2000_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2"

}

| 120

| 563

|

2000

|

T1

|

4

| null |

APMO

|

Let $n, k$ be given positive integers with $n>k$. Prove that

$$

\frac{1}{n+1} \cdot \frac{n^{n}}{k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}}<\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}<\frac{n^{n}}{k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}} .

$$

|

The inequality is equivalent to

$$

\frac{n^{n}}{n+1}<\binom{n}{k} k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}<n^{n}

$$

which suggests investigating the binomial expansion of

$$

n^{n}=((n-k)+k)^{n}=\sum_{i=0}^{n}\binom{n}{i}(n-k)^{n-i} k^{i}

$$

The $(k+1)$ th term $T_{k+1}$ of the expansion is $\binom{n}{k} k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}$, and all terms in the expansion are positive, which implies the right inequality.

Now, for $1 \leq i \leq n$,

$$

\frac{T_{i+1}}{T_{i}}=\frac{\binom{n}{i}(n-k)^{n-i} k^{i}}{\binom{n}{i-1}(n-k)^{n-i+1} k^{i-1}}=\frac{(n-i+1) k}{i(n-k)}

$$

and

$$

\frac{T_{i+1}}{T_{i}}>1 \Longleftrightarrow(n-i+1) k>i(n-k) \Longleftrightarrow i<k+\frac{k}{n} \Longleftrightarrow i \leq k

$$

This means that

$$

T_{1}<T_{2}<\cdots<T_{k+1}>T_{k+2}>\cdots>T_{n+1}

$$

that is, $T_{k+1}=\binom{n}{k} k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}$ is the largest term in the expansion. The maximum term is greater that the average, which is the sum $n^{n}$ divided by the quantity $n+1$, therefore

$$

\binom{n}{k} k^{k}(n-k)^{n-k}>\frac{n^{n}}{n+1}

$$

as required.

Comment: If we divide further by $n^{n}$ one finds

$$

\frac{1}{n+1}<\binom{n}{k}\left(\frac{k}{n}\right)^{k}\left(1-\frac{k}{n}\right)^{n-k}<1

$$

The middle term is the probability $P(X=k)$ of $k$ successes in a binomial distribution with $n$ trials and success probability $p=\frac{k}{n}$. The right inequality is immediate from the fact that $P(X=k)$ is not the only possible event in this distribution, and the left inequality comes from the fact that the mode of the binomial distribution are given by $\lfloor(n+1) p\rfloor=\left\lfloor(n+1) \frac{k}{n}\right\rfloor=k$ and $\lceil(n+1) p-1\rceil=k$. However, the proof of this fact is identical to the above solution.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2000_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 82

| 639

|

2000

|

T1

|

5

| null |

APMO

|

Given a permutation $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ of the sequence $0,1, \ldots, n$. A transposition of $a_{i}$ with $a_{j}$ is called legal if $a_{i}=0$ for $i>0$, and $a_{i-1}+1=a_{j}$. The permutation $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ is called regular if after a number of legal transpositions it becomes $(1,2, \ldots, n, 0)$. For which numbers $n$ is the permutation $(1, n, n-1, \ldots, 3,2,0)$ regular?

Answer: $n=2$ and $n=2^{k}-1, k$ positive integer.

|

A legal transposition consists of looking at the number immediately before 0 and exchanging 0 and its successor; therefore, we can perform at most one legal transposition to any permutation, and a legal transposition is not possible only and if only 0 is preceded by $n$.

If $n=1$ or $n=2$ there is nothing to do, so $n=1=2^{1}-1$ and $n=2$ are solutions. Suppose that $n>3$ in the following.

Call a pass a maximal sequence of legal transpositions that move 0 to the left. We first illustrate what happens in the case $n=15$, which is large enough to visualize what is going on. The first pass is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,0) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,5,4,0,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,7,6,0,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,9,8,0,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,11,10,0,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,13,12,0,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,15,14,0,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3) \\

& (1,0,14,15,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,2,3)

\end{aligned}

$$

After exchanging 0 and 2, the second pass is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,14,15,12,13,10,11,8,9,6,7,4,5,0,3) \\

& (1,2,14,15,12,13, \mathbf{1 0}, 11,8,9,0,7,4,5,6,3) \\

& (1,2, \mathbf{1 4}, 15,12,13,0,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,3) \\

& (1,2,0,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,3)

\end{aligned}

$$

After exchanging 0 and 3 , the third pass is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,7,4,5,6,0) \\

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,11,8,9,10,0,4,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,15,12,13,14,0,8,9,10,11,4,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,0,12,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,4,5,6,7)

\end{aligned}

$$

After exchanging 0 and 4, the fourth pass is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1,2,3,4,12,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,0,5,6,7) \\

& (1,2,3,4,0,13,14,15,8,9,10,11,12,5,6,7)

\end{aligned}

$$

And then one can successively perform the operations to eventually find

$$

(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,0,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15)

$$

after which 0 will move one unit to the right with each transposition, and $n=15$ is a solution. The general case follows.

Case 1: $n>2$ even: After the first pass, in which 0 is transposed successively with $3,5, \ldots, n-1$, after which 0 is right after $n$, and no other legal transposition can be performed. So $n$ is not a solution in this case.

Case 2: $n=2^{k}-1$ : Denote $N=n+1, R=2^{r},[a: b]=(a, a+1, a+2, \ldots, b)$, and concatenation by a comma. Let $P_{r}$ be the permutation

$$

[1: R-1],(0),[N-R: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R-1], \ldots,[2 R: 3 R-1],[R: 2 R-1]

$$

$P_{r}$ is formed by the blocks $[1: R-1],(0)$, and other $2^{k-r}-1$ blocks of size $R=2^{r}$ with consecutive numbers, beginning with $t R$ and finishing with $(t+1) R-1$, in decreasing order of $t$. Also define $P_{0}$ as the initial permutation.

Then it can be verified that $P_{r+1}$ is obtained from $P_{r}$ after a number of legal transpositions: it can be easily verified that $P_{0}$ leads to $P_{1}$, as 0 is transposed successively with $3,5, \ldots, n-1$, shifting cyclically all numbers with even indices; this is $P_{1}$.

Starting from $P_{r}, r>0$, 0 is successively transposed with $R, 3 R, \ldots, N-R$. The numbers $0, N-R, N-3 R, \ldots, 3 R, R$ are cyclically shifted. This means that $R$ precedes 0 , and the blocks become

$$

\begin{gathered}

{[1: R],(0),[N-R+1: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R],[N-3 R+1: N-2 R-1], \ldots,} \\

{[3 R+1: 4 R-1],[2 R: 3 R],[R+1: 2 R-1]}

\end{gathered}

$$

Note that the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number.

Now $0, N-R+1, N-3 R+1, \ldots, 3 R+1, R+1$ are shifted. Note that, for every $i$ th block, $i$ odd greater than 1 , the first number is cyclically shifted, and the blocks become

$$

\begin{gathered}

{[1: R+1],(0),[N-R+2: N-1],[N-2 R: N-R+1],[N-3 R+2: N-2 R-1], \ldots,} \\

{[3 R+1: 4 R-1],[2 R: 3 R+1],[R+2: 2 R-1]}

\end{gathered}

$$

The same phenomenom happened: the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number. This pattern continues: $0, N-R+u, N-3 R+u, \ldots, R+u$ are shifted, $u=0,1,2, \ldots, R-1$, the first block and the ones on even positions greater than 2 have one more number and the other blocks have one less number, until they vanish. We finish with

$$

[1: 2 R-1],(0),[N-2 R: N-1], \ldots,[2 R: 4 R-1]

$$

which is precisely $P_{r+1}$.

Since $P_{k}=[1: N-1],(0), n=2^{k}-1$ is a solution.

Case 3: $n$ is odd, but is not of the form $2^{k}-1$. Write $n+1$ as $n+1=2^{a}(2 b+1), b \geq 1$, and define $P_{0}, \ldots, P_{a}$ as in the previous case. Since $2^{a}$ divides $N=n+1$, the same rules apply, and we obtain $P_{a}$ :

$$

\left[1: 2^{a}-1\right],(0),\left[N-2^{a}: N-1\right],\left[N-2^{a+1}: N-2^{a}-1\right], \ldots,\left[2^{a+1}: 3 \cdot 2^{a}-1\right],\left[2^{a}: 2^{a+1}-1\right]

$$

But then 0 is transposed with $2^{a}, 3 \cdot 2^{a}, \ldots,(2 b-1) \cdot 2^{a}=N-2^{a+1}$, after which 0 is put immediately after $N-1=n$, and cannot be transposed again. Therefore, $n$ is not a solution. All cases were studied, and so we are done.

Comment: The general problem of finding the number of regular permutations for any $n$ seems to be difficult. A computer finds the first few values

$$

1,2,5,14,47,189,891,4815,29547

$$

which is not catalogued at oeis.org.

|

{

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2000_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n\n"

}

| 187

| 2,361

|

2002

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be a sequence of non-negative integers, where $n$ is a positive integer.

Let

$$

A_{n}=\frac{a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}}{n}

$$

Prove that

$$

a_{1}!a_{2}!\ldots a_{n}!\geq\left(\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor!\right)^{n}

$$

where $\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor$ is the greatest integer less than or equal to $A_{n}$, and $a!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times a$ for $a \geq 1$ (and $0!=1$ ). When does equality hold?

|

Assume without loss of generality that $a_{1} \geq a_{2} \geq \cdots \geq a_{n} \geq 0$, and let $s=\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor$. Let $k$ be any (fixed) index for which $a_{k} \geq s \geq a_{k+1}$.

Our inequality is equivalent to proving that

$$

\frac{a_{1}!}{s!} \cdot \frac{a_{2}!}{s!} \cdot \ldots \cdot \frac{a_{k}!}{s!} \geq \frac{s!}{a_{k+1}!} \cdot \frac{s!}{a_{k+2}!} \cdot \ldots \cdot \frac{s!}{a_{n}!}

$$

Now for $i=1,2, \ldots, k, a_{i}!/ s!$ is the product of $a_{i}-s$ factors. For example, 9!/5! $=9 \cdot 8 \cdot 7 \cdot 6$. The left side of inequality (1) therefore is the product of $A=a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}-k s$ factors, all of which are greater than $s$. Similarly, the right side of (1) is the product of $B=(n-k) s-$ $\left(a_{k+1}+a_{k+2}+\cdots+a_{n}\right)$ factors, all of which are at most $s$. Since $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}=n A_{n} \geq n s, A \geq B$. This proves the inequality. [ 5 marks to here.]

Equality in (1) holds if and only if either:

(i) $A=B=0$, that is, both sides of (1) are the empty product, which occurs if and only if $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$; or

(ii) $a_{1}=1$ and $s=0$, that is, the only factors on either side of (1) are 1 's, which occurs if and only if $a_{i} \in\{0,1\}$ for all $i$. [2 marks for both (i) and (ii), no marks for (i) only.]

|

{

"problem_match": "\n1. ",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2002_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1."

}

| 189

| 537

|

2002

|

T1

|

1

| null |

APMO

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be a sequence of non-negative integers, where $n$ is a positive integer.

Let

$$

A_{n}=\frac{a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}}{n}

$$

Prove that

$$

a_{1}!a_{2}!\ldots a_{n}!\geq\left(\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor!\right)^{n}

$$

where $\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor$ is the greatest integer less than or equal to $A_{n}$, and $a!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times a$ for $a \geq 1$ (and $0!=1$ ). When does equality hold?

|

Assume without loss of generality that $0 \leq a_{1} \leq a_{2} \leq \cdots \leq a_{n}$. Let $d=a_{n}-a_{1}$ and $m=\left|\left\{i: a_{i}=a_{1}\right\}\right|$. Our proof is by induction on $d$.

We first do the case $d=a_{n}-a_{1}=0$ or 1 separately. Then $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{m}=a$ and $a_{m+1}=\cdots=a_{n}=a+1$ for some $1 \leq m \leq n$ and $a \geq 0$. In this case we have $\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor=a$, so the inequality to be proven is just $a_{1}!a_{2}!\ldots a_{n}!\geq(a!)^{n}$, which is obvious. Equality holds if and only if either $m=n$, that is, $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}=a$; or if $a=0$, that is, $a_{1}=\cdots=a_{m}=0$ and $a_{m+1}=\cdots=a_{n}=1$. [ 2 marks to here.]

So assume that $d=a_{n}-a_{1} \geq 2$ and that the inequality holds for all sequences with smaller values of $d$, or with the same value of $d$ and smaller values of $m$. Then the sequence

$$

a_{1}+1, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots, a_{n-1}, a_{n}-1

$$

though not necessarily in non-decreasing order any more, does have either a smaller value of $d$, or the same value of $d$ and a smaller value of $m$, but in any case has the same value of $A_{n}$. Thus, by induction and since $a_{n}>a_{1}+1$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{1}!a_{2}!\ldots a_{n}! & =\left(a_{1}+1\right)!a_{2}!\ldots a_{n-1}!\left(a_{n}-1\right)!\cdot \frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}+1} \\

& \geq\left(\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor!\right)^{n} \cdot \frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}+1} \\

& >\left(\left\lfloor A_{n}\right\rfloor!\right)^{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

which completes the proof. Equality cannot hold in this case.

|

{

"problem_match": "\n1. ",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2002_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2."

}

| 189

| 628

|

2002

|

T1

|

2

| null |

APMO

|

Find all positive integers $a$ and $b$ such that

$$

\frac{a^{2}+b}{b^{2}-a} \text { and } \frac{b^{2}+a}{a^{2}-b}

$$

are both integers.

|

By the symmetry of the problem, we may suppose that $a \leq b$. Notice that $b^{2}-a \geq 0$, so that if $\frac{a^{2}+b}{b^{2}-a}$ is a positive integer, then $a^{2}+b \geq b^{2}-a$. Rearranging this inequality and factorizing, we find that $(a+b)(a-b+1) \geq 0$. Since $a, b>0$, we must have $a \geq b-1$. [3 marks to here.] We therefore have two cases:

Case 1: $a=b$. Substituting, we have

$$

\frac{a^{2}+a}{a^{2}-a}=\frac{a+1}{a-1}=1+\frac{2}{a-1},

$$

which is an integer if and only if $(a-1) \mid 2$. As $a>0$, the only possible values are $a-1=1$ or 2. Hence, $(a, b)=(2,2)$ or $(3,3)$. [1 mark.]

Case 2: $a=b-1$. Substituting, we have

$$

\frac{b^{2}+a}{a^{2}-b}=\frac{(a+1)^{2}+a}{a^{2}-(a+1)}=\frac{a^{2}+3 a+1}{a^{2}-a-1}=1+\frac{4 a+2}{a^{2}-a-1} .

$$

Once again, notice that $4 a+2>0$, and hence, for $\frac{4 a+2}{a^{2}-a-1}$ to be an integer, we must have $4 a+2 \geq a^{2}-a-1$, that is, $a^{2}-5 a-3 \leq 0$. Hence, since $a$ is an integer, we can bound $a$ by $1 \leq \bar{a} \leq 5$. Checking all the ordered pairs $(a, b)=(1,2),(2,3), \ldots,(5,6)$, we find that only $(1,2)$ and $(2,3)$ satisfy the given conditions. [3 marks.]

Thus, the ordered pairs that work are

$$

(2,2),(3,3),(1,2),(2,3),(2,1),(3,2)

$$

where the last two pairs follow by symmetry. [2 marks if these solutions are found without proof that there are no others.]

|

{

"problem_match": "\n2. ",

"resource_path": "APMO/segmented/en-apmo2002_sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

| 59

| 570

|

2002

|

T1

|

3

| null |

APMO

|